The

Wooden Economy

or

Logistic solutions for Lutemakers

The

very name of the lute comes from the Arabic Al’Ud, or the wood, and this paper

deals with some historic aspects of the supply of the woods necessary and some

ideas about the quantities involved.

It

is evident from iconography and literary references that the lute was widely

used across all of W. Europe very soon after its arrival as the ‘Ud in about

1250. This alone may cast some doubt on a single entry point in Moorish Spain,

undoubtedly important as that was. Here it is in Seville in 1283

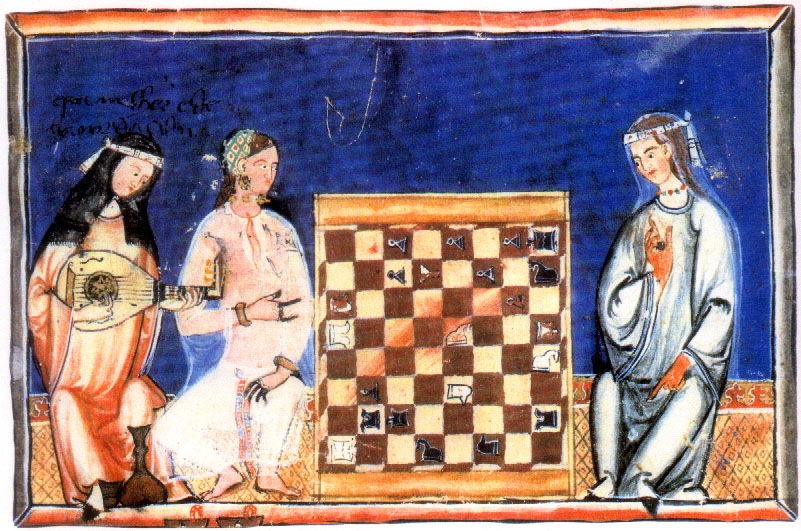

Alphonso

el Sabio book of chess endgames 1283

By

1300 it was in England and common enough to be used prominently in this

ecclesiastical cope.

Steeple

Aston Cope c.1310-1340 (Opus Anglicanum) earliest known English representation

of a lute. V&A London

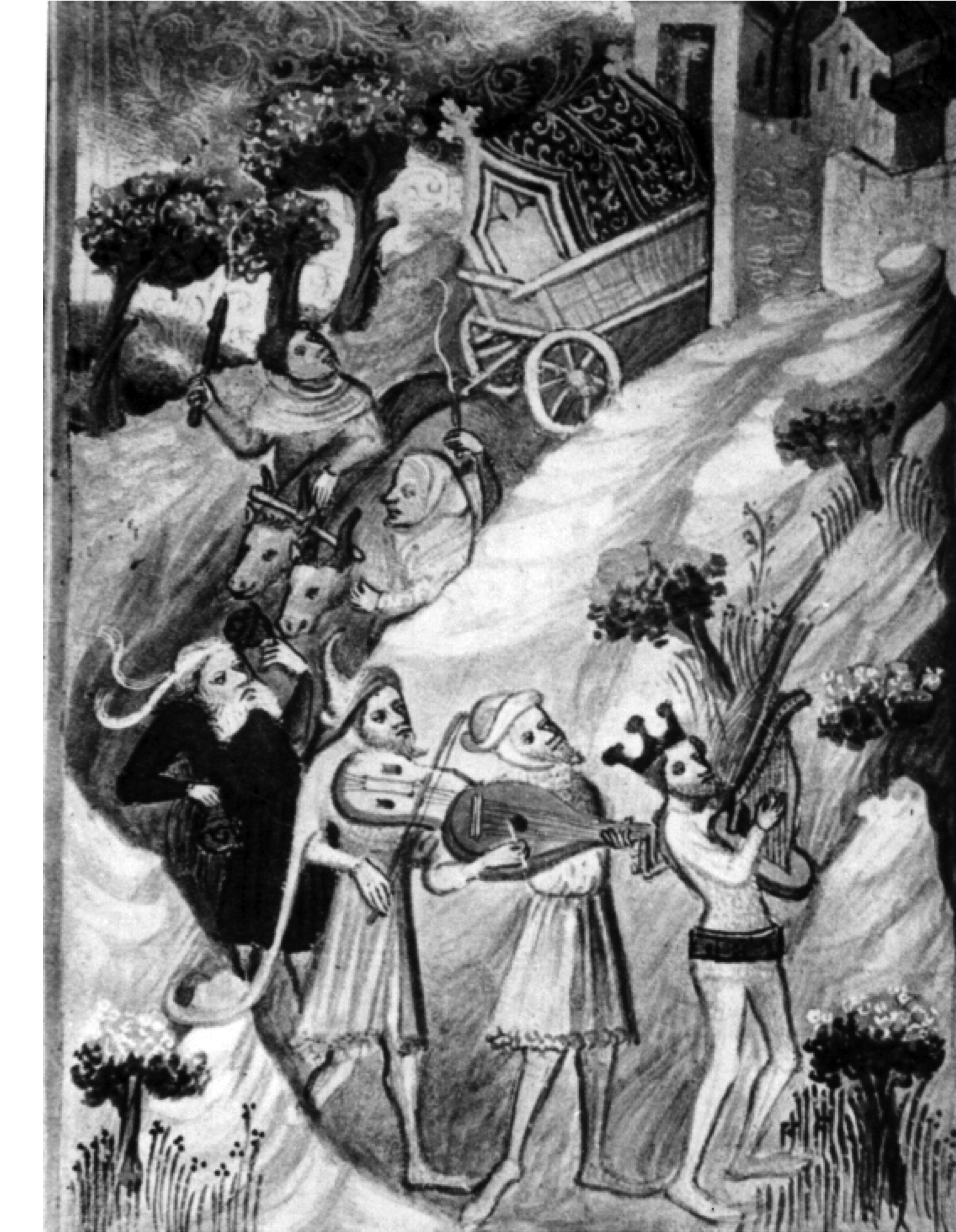

In c. 1340

here it is in the Wenceslas Bible from Bohemia

Wenceslas

IV bible (Czech 1387-1400) Vienna Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek MS

2759/64, fol. 81

At

the same time, c.1340, here it is in Florence.

Andrea

Pisano (c.1290-1348) successor to Giotto on Florence campanile Orpheus as

luteplayer c.1340

Circa

1370 here is another more up-to-date looking lute also in Florence

Agnolo

Gaddi,

The Coronation of the Virgin, probably c. 1370

Samuel

H. Kress Collection 1939.1.203

In

1375 it was in an explicitly Christian context in Spain

Circa

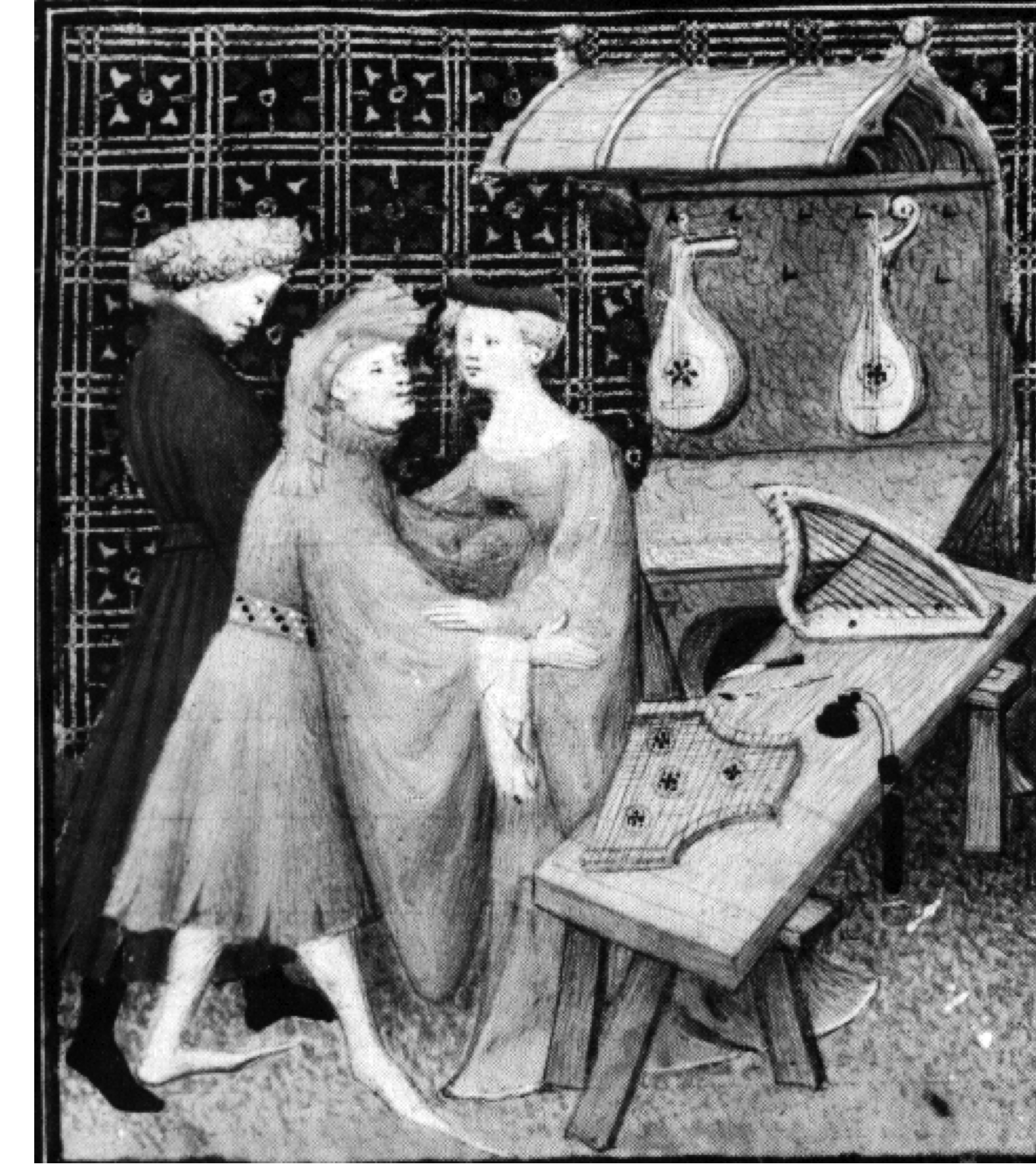

1400 we even have an idealised picture of a lutemaker’s workshop and sales

showroom in France!

Boccaccio,

Des cleres et nobles femmes (French after 1401) Bibliotheque nationale, MS fr.

12420, fol. 119

In

1440 here it is in Italy

And

in 1450 in the Netherlands

Where

were all these medieval lutes being made? We simply don’t know. Perhaps all

locally, certainly there must have been some local lutemaking for Henri Arnault

of Zwolle to find out enough general details to write his manuscript

description in Dijon round about 1440, when he was employed as physician and

astronomer for Phillip The Good, Duke of Burgundy. But it is somewhat surprising that it is not

until 1461 that we get the first mention of a lutemaker, Perchtold, in the

Füssen area and the first lutemaker to acquire citizenship there is a certain

Georg Wolf in 1493, because Füssen was to become such a dominant centre of

lutemaking in the next century. Perhaps it already was, but we don’t know. (The

director of the Museum in Füssen somewhat mischievously suggests the date 1493

and the name Wolf might suggest he was a jewish maker originally called Lopez

expelled from Spain, Lopez-Lupo-Wolf.)

Certainly

moving wood in the past was both difficult and expensive, so industries tended

to grow up near to this natural resource and with onward transport links to a

market. So it is perhaps no surprise that the first recorded major centre of

lutemaking did establish itself in the area round Füssen, right on the edge of

the heavily forested Alps with its abundant supplies of spruce [picea abies]

for soundboards, yew [taxus baccata] and maple [acer platanoides & acer

pseudoplatanus] for the backs and structural parts of lutes. There was also plenty of plum [prunus spp.]

for pegs and bridges.

Matthäus

Merian copperplate 1643

The heavy,

bulky wood needed only to be brought down the mountainsides which begin in the

foreground of this view just across the river Lech from Füssen, while the river

itself afforded easy and gentle transport for the delicate finished instruments

towards their main markets in England, France, the Netherlands and Germany.

Situated on the Via Claudia, a

former Roman road, Füssen was on a route, that until the 1950s, was the major

connection between Augsburg and Venice. Though shallow the River Lech is

navigable by raft and joins the Danube providing a trading route to Vienna and

Budapest. By road or water merchants had easy - for the time - access to

rich markets to the south-west and the north-east.

Michael

Wening copperplate,1696

The

best spruce for soundboards needs tight grain with narrow rings and a sharp

division between summer and winter growth so the best are found at the higher

altitudes. The trees themselves need to be very large to allow for the wide

soundboards of lutes, plus the best time to harvest this wood is in the depths

of winter when the sap is lowest. So the process of extracting these large logs

across and down steep and rugged terrain was a real problem before the modern

mechanical era shown in my first photograph. The system devised, called

Sovenda, was described by a parson Hans

Rudolf Schintz in 1783 in his Beyträge zur näheren Kenntniss des

Schweizerlandes as a series of

timber slides held together not by fastenings but simply by pouring water over

the joints and allowing it to freeze.

J

R Schellenberg 1782

He

describes it as being peculiar to the Italian side of the Alps but it went on

until the late 19th century all over the Alps into the era of photographs, such

this from 1886 in Lower Engadin

And

we have a highly romantic description of the process written by H. Berlepsch, The Alps or Sketches of Life

and Nature in the Mountains. (Trans. Leslie Stephen 1861) pp.372-5

But

there is an even more interesting account of it in the 1884 Centralblatt für

das gesamte Forstwesen, X. Jahrgand, März, p.155 which was quoted by Remy

Gug in his wonderful article in FoHMRI comm 1101 Oct. 1990.

“Anyone

who has ever been near to a timber slide while it is being used has noticed a

remarkable difference in the sound of the sliding timber....There is no doubt

about the fact that this “singing timber” has always been in demand and that it

achieved a good price. .... If for example in Carinthia timber had been

prepared for transport, an Italian gentleman would show up, settle himself

nearby and listen attentively to the sound of the thundering timber. Whenever a

timber passed by that caused the air to vibrate his face lighted and he told

his servant to mark it. He recognised the sound from a great distance. Often he

would sit there and wait for hundreds of timber to pass. As soon as the singing

sound was heard he would be looking for the “singer” and found it at once. The

higher and longer the sound, the more he liked it. Thus he would wait for his

“singers” for many days.”

Remy

Gug notes that all this machinery of transport involved hundreds of experienced

men and would not be possible without well established traders with

considerable capital. Just as today, the lute and other instrument makers

relied on an existing logistical infrastructure designed to provide large quantities of timber for other

uses. Schintz estimates that 12,000 - 20,000 logs would be slid down the

mountainside each winter season, and a later article in Forest History

Today 2002 describes a similar 12

kilometer slide built in Alpnach 1810 which itself used 25,500 logs in its

construction alone.

However

all was not plain sailing for Füssen and its industry. In 1525 the Peasants War

broke out in South Germany and although many were killed in its suppression and

afterwards the survivors harshly taxed

in retribution, Füssen was not too badly affected. Dürer, as usual, has

a humane and ironic eye for the situation.

“If

someone wishes to erect a victory monument after vanquishing rebellious

peasants,.........”

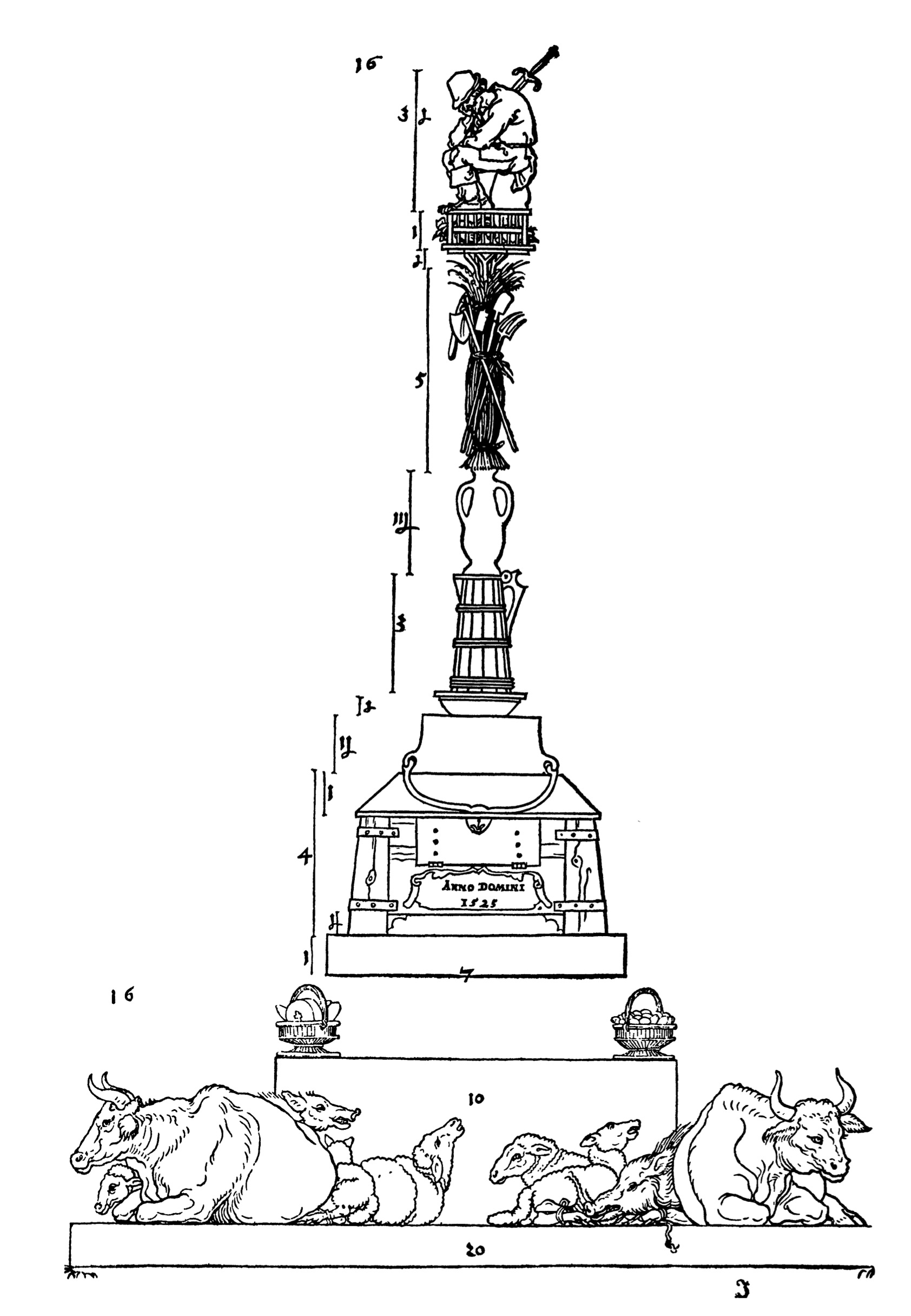

Albrecht

Dürer, Underweysung der Messung, Nürnberg 1525, Monument to Commemorate

a Victory over the Rebellious Peasants, 1525

Later

in 1546 the catholic town of Füssen was

caught on the wrong side of the religious Schmalkaldic War and was sacked by

15000 troops and 100 cartloads of loot was taken off to Augsburg. In addition

there were outbreaks of plague in 1520, 1524, 1536 as well as in 1546 after the

sack of the town. So the attractions of rich, relatively stable, catholic

northern Italy just over the Alps along the well-established old Roman route

Via Claudia Augusta must have been immense.

Certainly

about this time there emerge other important centres of lutemaking in North Italy,

Venice, Verona, Padua and Bologna, and ALL the makers have German names and

strong links back to the Füssen area.

The

most well-known maker is undoubtedly Laux Maler in Bologna and he seems to have

been one of the earliest to arrive probably even as early as 1503 according to

Sandro Pasquale & Roberto Regazzi who have produced a detailed study of the

Bolognese lutemakers (Le radici del successo della liuteria a Bologna,

Florenus Edizioni, 1998) Maler’s inventory taken a few days after his death in

1552 shows that he had an industrial scale workshop with about 1100 lutes of

various sorts in his workshop. The only raw materials noted are 1354 lute

soundboards in various stages of completion and unspecified numbers of lute

ribs. but no large pieces of raw timber. As I have suggested the raw timber is

too bulky for long distance transport so it is better to select higher up the

chain and only transport the selected smaller pieces.

There

is also another inventory of Christofolo Cocho from the really extensive

researches of Stefano Pio whose three volumes of work on the lute and violin

makers of Venice is a major contribution to our knowledge. But this inventory

is from 1664 when lutemakers were beginning to turn over to making violins, in

fact his workshop is called a violin bottega in the inventory.

So

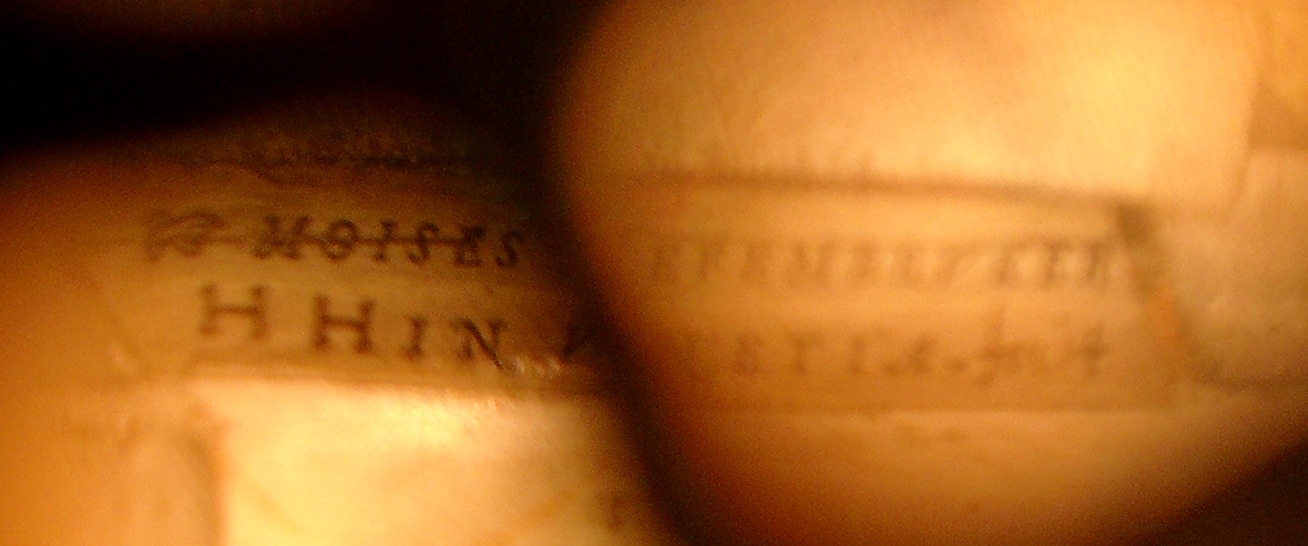

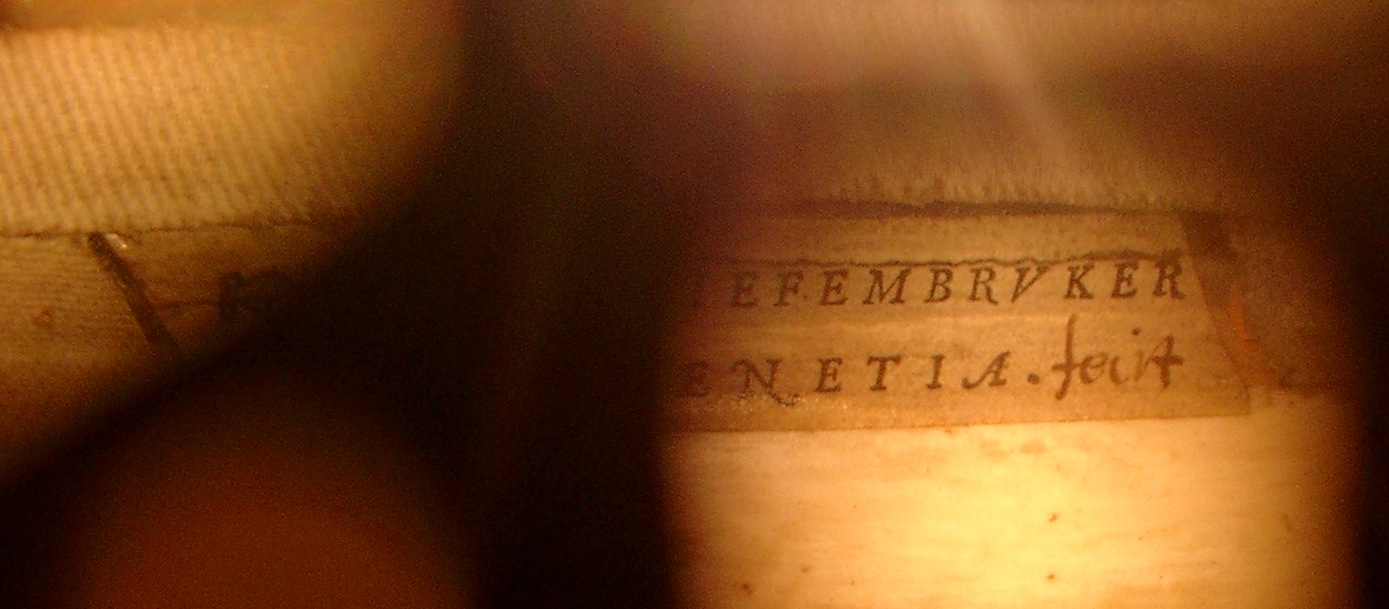

I shall concentrate on the third surviving inventory, that of Moises

Tiefembruker son of Magno Tieffenbrucker, (This is a minefield of

identification and it’s not entirely clear which of the Dieffopruchar labelled

lutes can be attributed to which individual) another German with a name

connecting him back to Tieffenbruck near Füssen. I have worked on this with Francesco Conto

and it is highly revealing of the industrial scale of the trade.

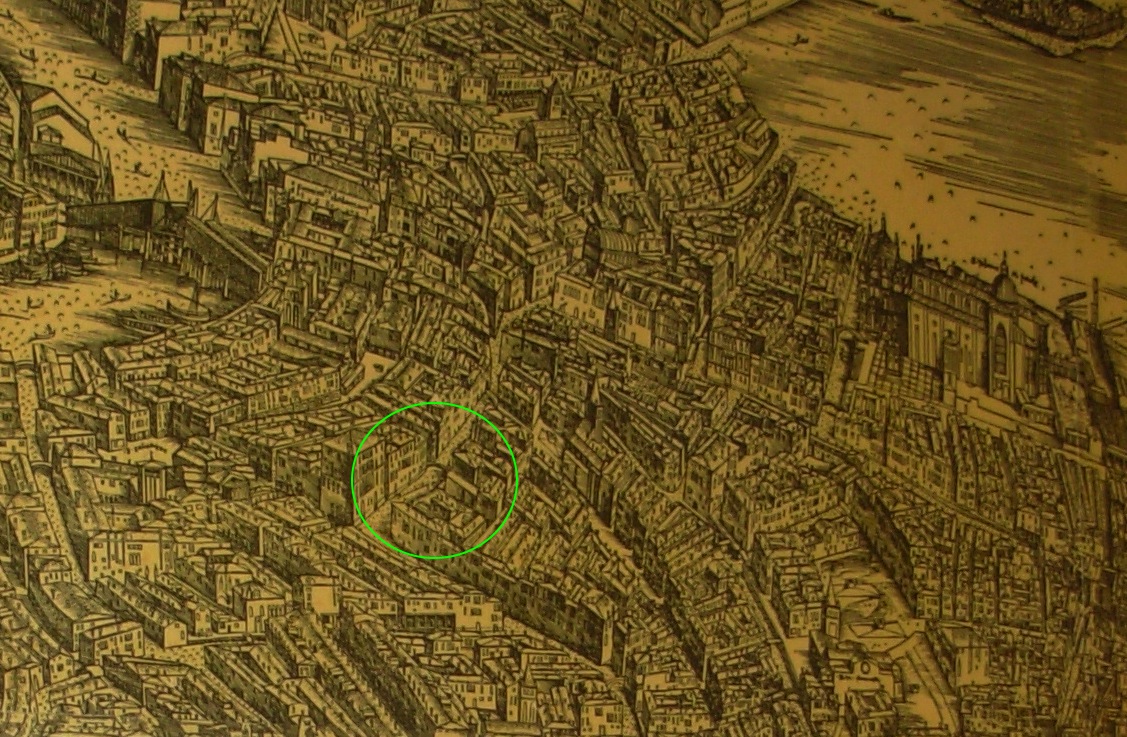

He

lived here in Calle dei Stagneri [alley of the tinsmiths] shown in the Jacopo

de Barbari map of 1500

Jacopo

de’Barbari, Bird’s Eye View of Venice, 1500, British Museum.

And

here it is today, recognisably the same.

Google

image

This

the building with the bridge leading from the calle dei Stagneri

Photo,

David Van Edwards

with

the water entrance, mentioned in the inventory

Photo,

David Van Edwards

His

inventory is dated 1581 There were two versions taken within days of each other

by Loredan one of the most prestigious law firms in Venice, presumably there

was some dispute. This is a summary of the lute related parts of the second

more detailed version, translated by Francesco Contó.

140

lutes of yew and figured maple

12

lutes with ivory lines

100

cheap lutes

110

yew lutes and others

10

ivory and sandalwood lutes

(from

the first inventory I include: 1 lute in black sandalwood and ivory with its

own case.)

4

ivory lutes

Total

376 lutes of which 26 expensive and 100 cheap

36

unfinished lutes

150

yew lute backs

24

cheap lute backs

Total

174 lute backs of which 150 yew

8

guitars

1400

yew ribs

6100

yew ribs

1300

yew ribs

6000

yew ribs

Total

14,800 yew ribs

400

bad yew ribs

400

sandalwood ribs

1400

white wood ribs to be planed (poplar?)

Grand

Total 17,000 ribs

2000

soundboards for lute and guitar

600

lute necks

300

bridges

150

fingerboards

160

ivory pegs

170

lute cases, lined and unlined

10,800

lute and violin strings

480

thin strings

1200

bad strings

Total

12,480 strings

10

cornetti

8

pieces of ebony

19

ivory tusks

40

lute and guitar moulds

90

locks for lute (cases)

Sharpening

stone and some iron tools and some lute moulds

I

want to flag up a few points:

1.

Again a large number of finished lutes but virtually no tools, just the 40+

moulds, suggesting he was employing journeymen, Gazellen, who would have had

their own tools.

2.

The explicit distinction between cheap and expensive lutes.

3.

The colossal number of yew ribs which were clearly already planed, in contrast

to the 1400 white wood ribs which were unplaned. I think this suggests these

were local wood, perhaps maple but perhaps poplar.

4.

Again a huge number of soundboards identified as such, not logs of spruce.

5.

Ivory both as tusks and as ribs. This and the ebony logs probably valuable

enough to import in the lump.

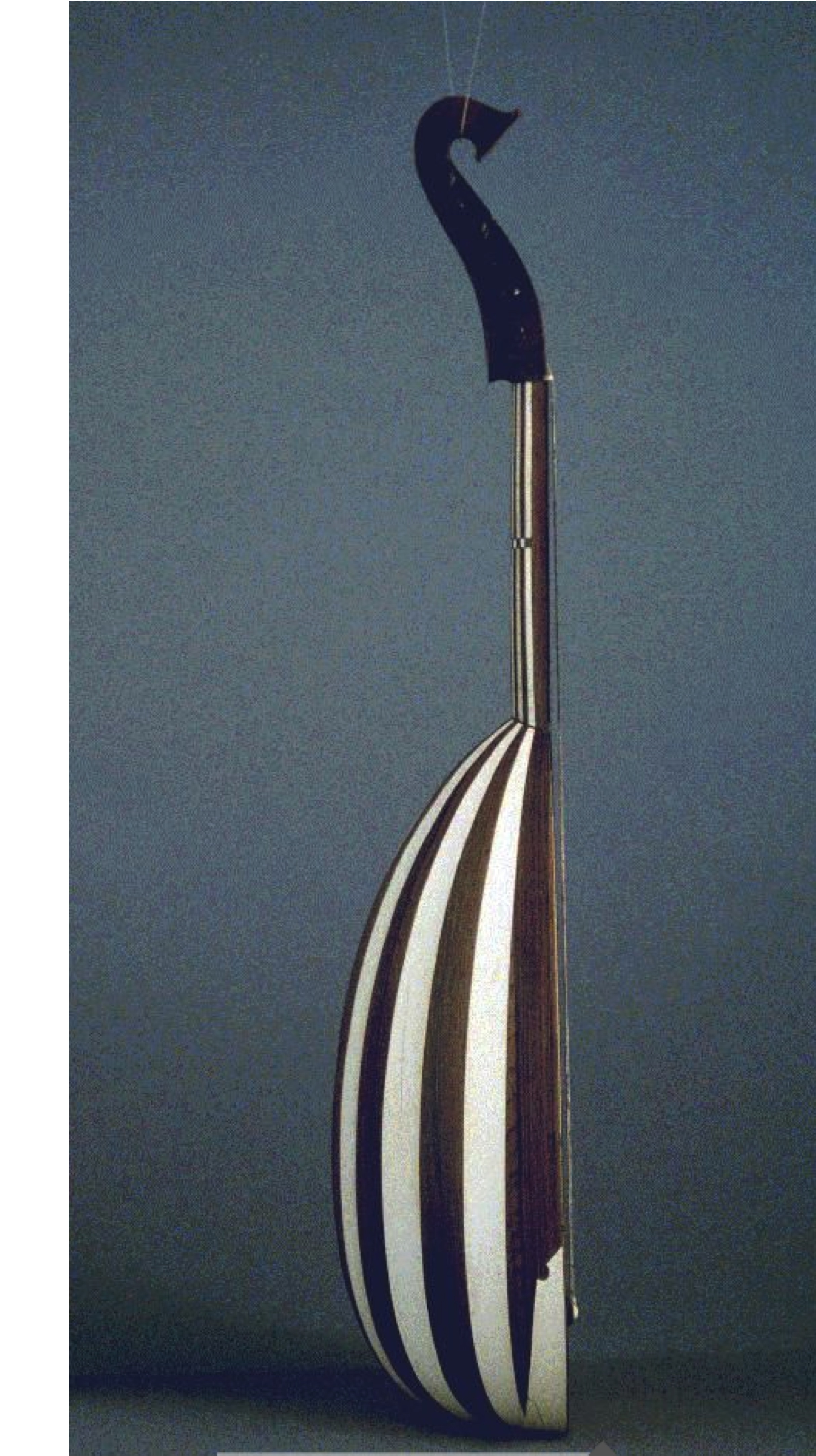

There

are two surviving lutes with his identical printed labels and, neatly, one is

expensive and the other clearly cheap.

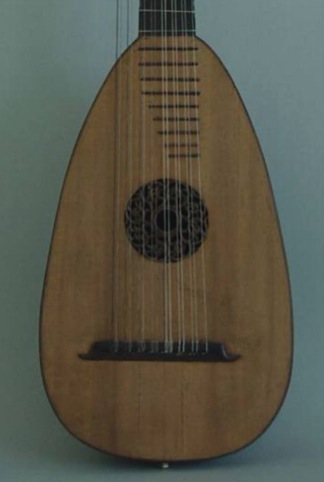

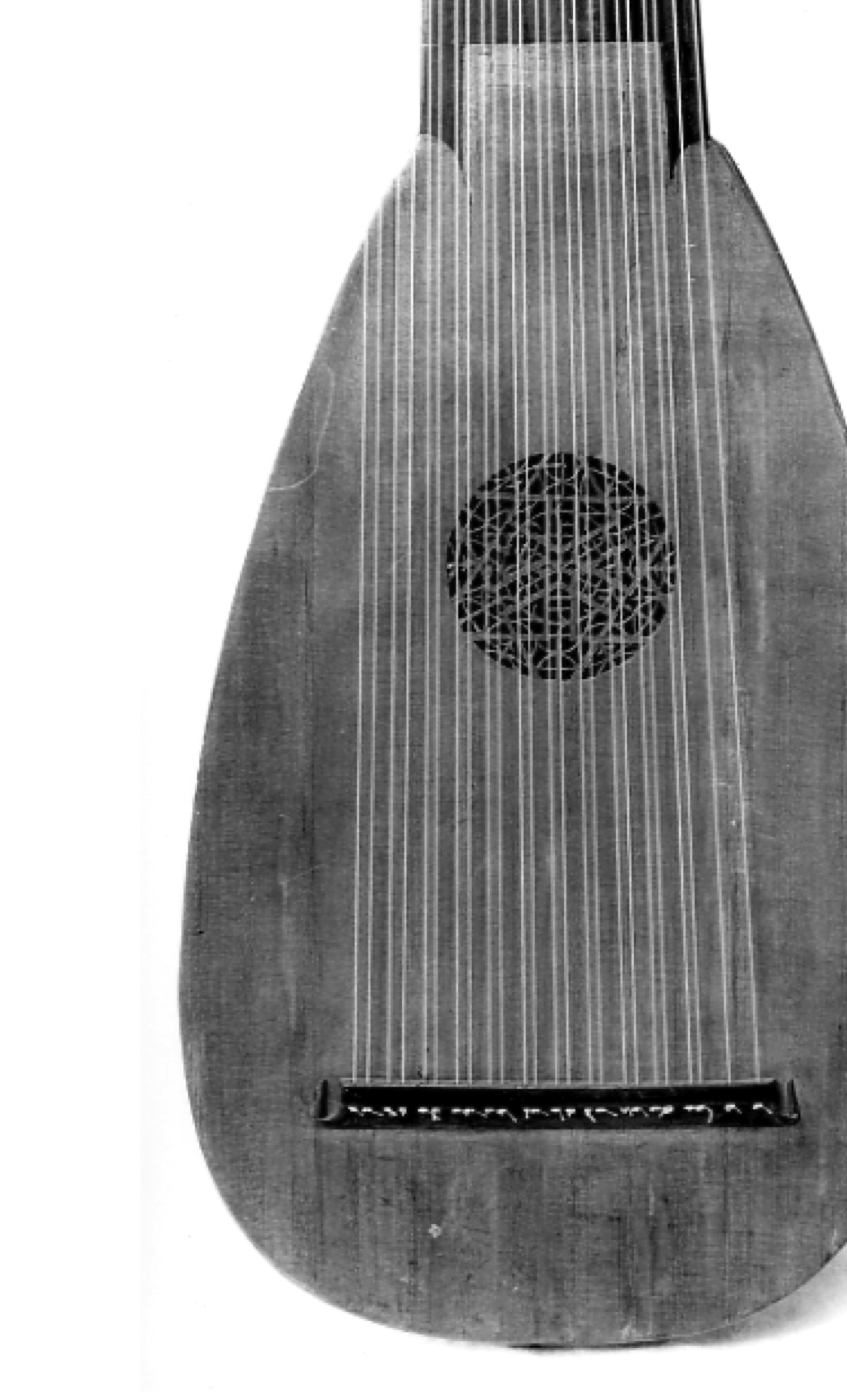

I’ll

start at the bottom end of the market. This is the lute in Munich Stadt Museum,

it has been sadly converted into a mandora

Photo,

David Van Edwards

For

the present purpose it is interesting that it is, unusually cheap and is made

of poplar, a cheap white wood readily available in North Italy. It is also of

the slightly older Maler type shape, long and pear shaped.

Photo,

David Van Edwards

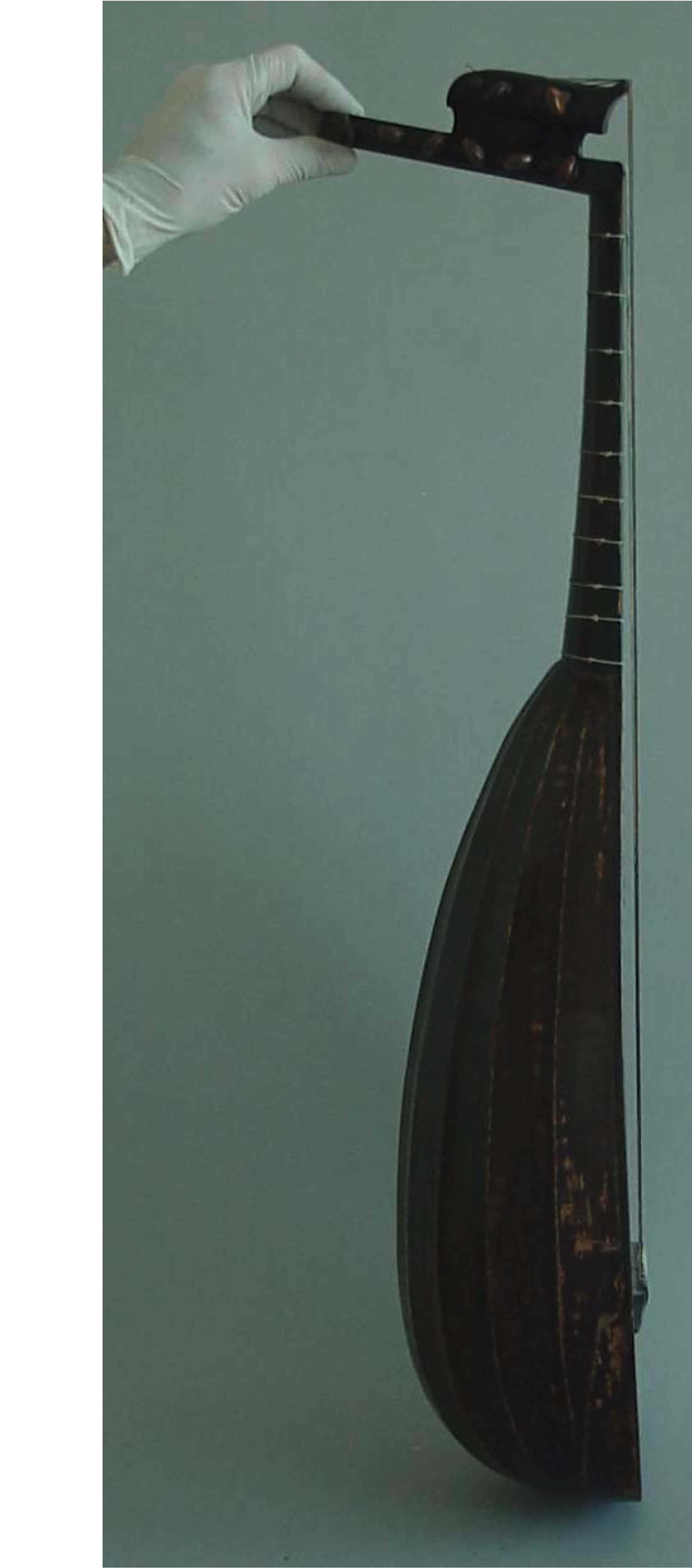

Moises

side view

Maler

side view

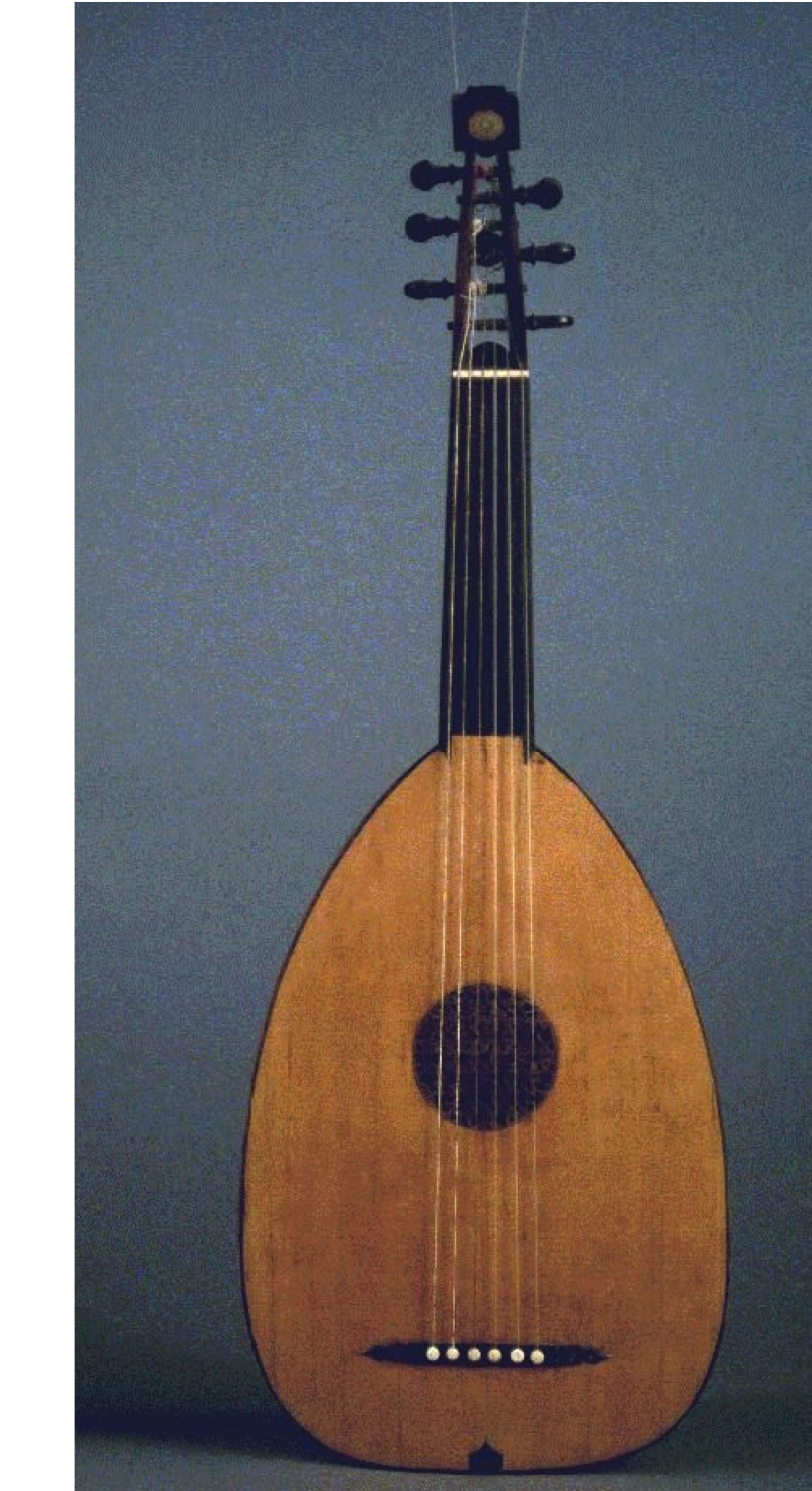

Now

here is the up-market lute, this has a handwritten addition of HH and fecit

suggesting it was actually made by a senior journeyman who was allowed some

identity.

Moises

side view

Florence

Bardini Museum 144 Magno Dieffopruchar, Venice, 1609 side view

Moises front view

Florence

Bardini Museum 144 Magno Dieffopruchar, Venice, 1609 front view

Musée

de la Musique, Paris (E. 1560)

Again

converted to a mandora but this one is made of ivory and Rio rosewood

[Dalbergia nigra] and calls to mind the item:

“1 lute in black

sandalwood and ivory with its own case.”

Now there is no such wood

as black sandalwood. Sandalwood [santalum album] is a light, soft, fragrant

wood rather yellowish. I notice that there are 400 sandalwood ribs in the

inventory and indeed the famous 1566 Fugger inventory of lutes has four lutes of

sandalwood and five lutes made of striped sandalwood and ivory so all these

might indeed be what we know of as sandalwood, even though it does not strike

me as a very suitable wood for a lute back. However the smell might well have

appealed to a rich collector like Raymond Fugger.

But if you are a dealer

or a maker in Venice encountering Rio rosewood [dalbergia nigra] for the first

time you might well notice the smell as well as the colour and put the two

together in the name black sandalwood. Similar things have happened when naming

US woods. In fact there is another name for this wood, Palisander, This word

can’t be traced back further than the 18th century

and it first appears in Dutch. When I consult the etymology it is very much

disputed, with several people suggesting it came from the Spanish, Palo Santo

the holy wood or lignum vitae [Guaiacum] so called because it was widely used

as a cure for the French pox - that is syphilis! However the Dutch knew this

wood very well as pockhoudt or pox wood and were therefore very unlikely to

confuse the two. In support of my supposition I have found that Corominas, Joan

& Jose A Pascual 1980-3 in their Diccionario Critico Etimologico

Castellano e Hispanico. Madrid: Editorial Gredos

(1981:4:354)

suggest it comes from Palo sándal ie.

sandalwood, on account of the smell.

What

is clear both from the inventory and surviving lutes in museums is that South

American woods and other exotica like ivory and ebony were really in

surprisingly common use for lutes, even allowing for the fact that obviously

valuable instruemnts are more likely to survive through periods of disuse. In

the Fugger inventory there are lutes of Indian cane, whalebone, sandalwood,

lignum vitae, ebony, Brazil wood [possibly pernambuco] maple, cypress, and of

course yew, and there are several surviving lutes of snakewood and kingwood. It

is odd therefore that other instruments of the violin family did not seem to

experiment with this huge range of woods. I suggest it is because the violin

family was still mostly the preserve of the professional player whereas the

lute was an aspirational instrument which appealed to rich collectors and

amateurs as well as the few professionals. I very much doubt whether Dowland or

Francesco da Milano played on ebony or snakewood lutes, though Piccinini

reports that Caccini played an ivory lute. Acoustically too the back of a lute

is not so intimately connected to the soundboard as in the violin with its

soundpost, so the influence is more as a reflective surface and for this these

harder, heavier woods do increase the volume without changing the character as

they might in a violin.

But

the vast preponderance of ribs in Moises’ inventory are yew. There are no

surviving yew wood lutes by Moises but plenty by other makers, out of my

database of 800 lutes I have information on the ribs of 539, of these 140 have

yew ribs the second most common wood after the 173 of maple. And many of these

use the contrast betwen the pale sapwood and the orange brown heartwood of yew

to produce a striking striped effect that is not obtainable from any other

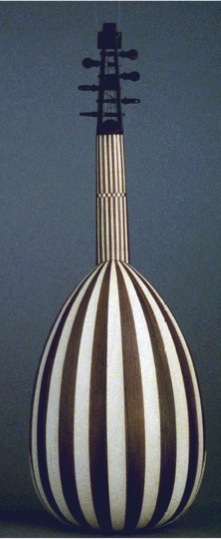

wood. This theorbo by Buechenberg, made in 1614, has 41 ribs of

heartwood/sapwood yew with ebony strips between the ribs.

Photo,

David Van Edwards

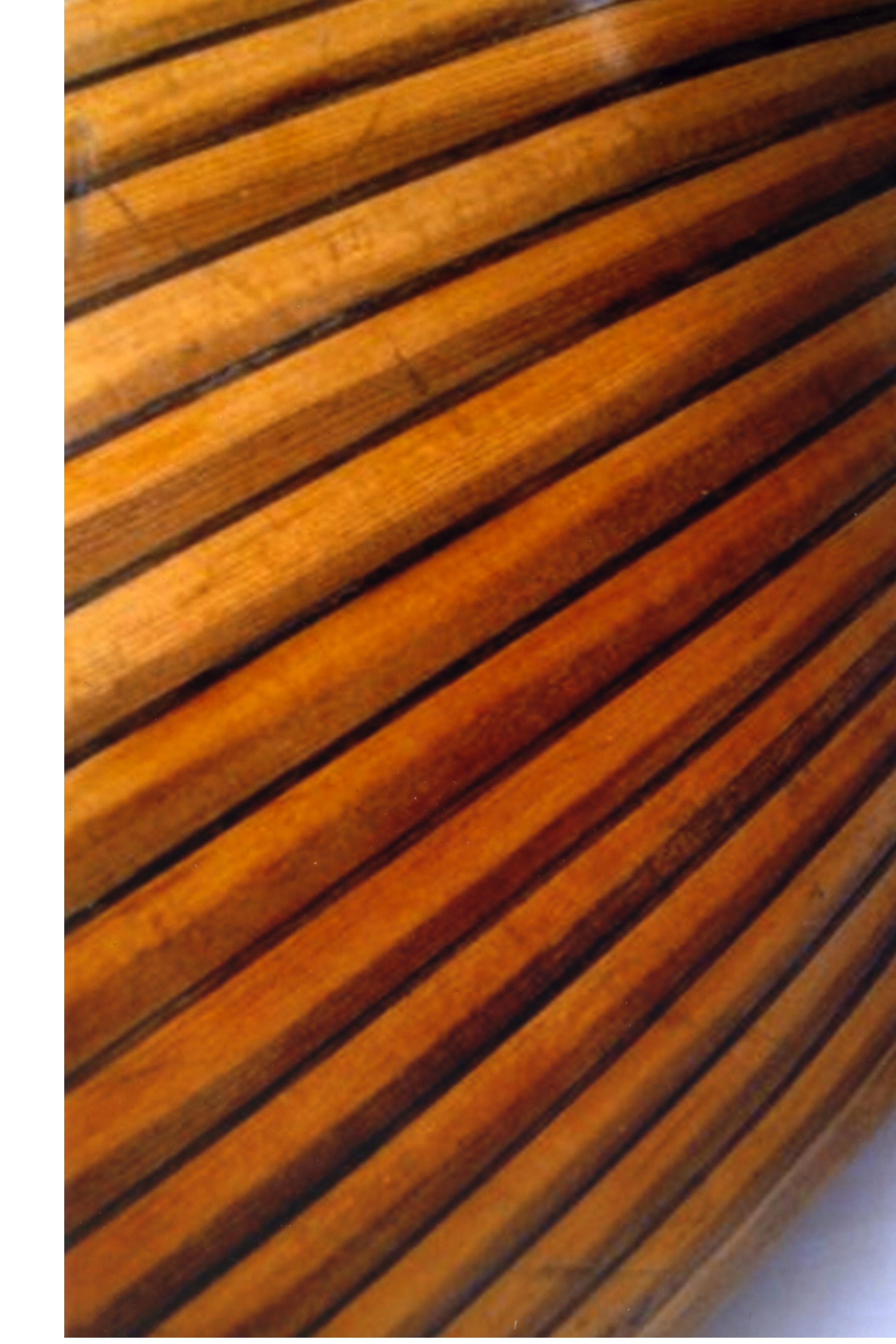

This

close-up shows the fine grain and you can clearly see how straight and blemish

free such wood must be to have the full effect

Photo,

David Van Edwards

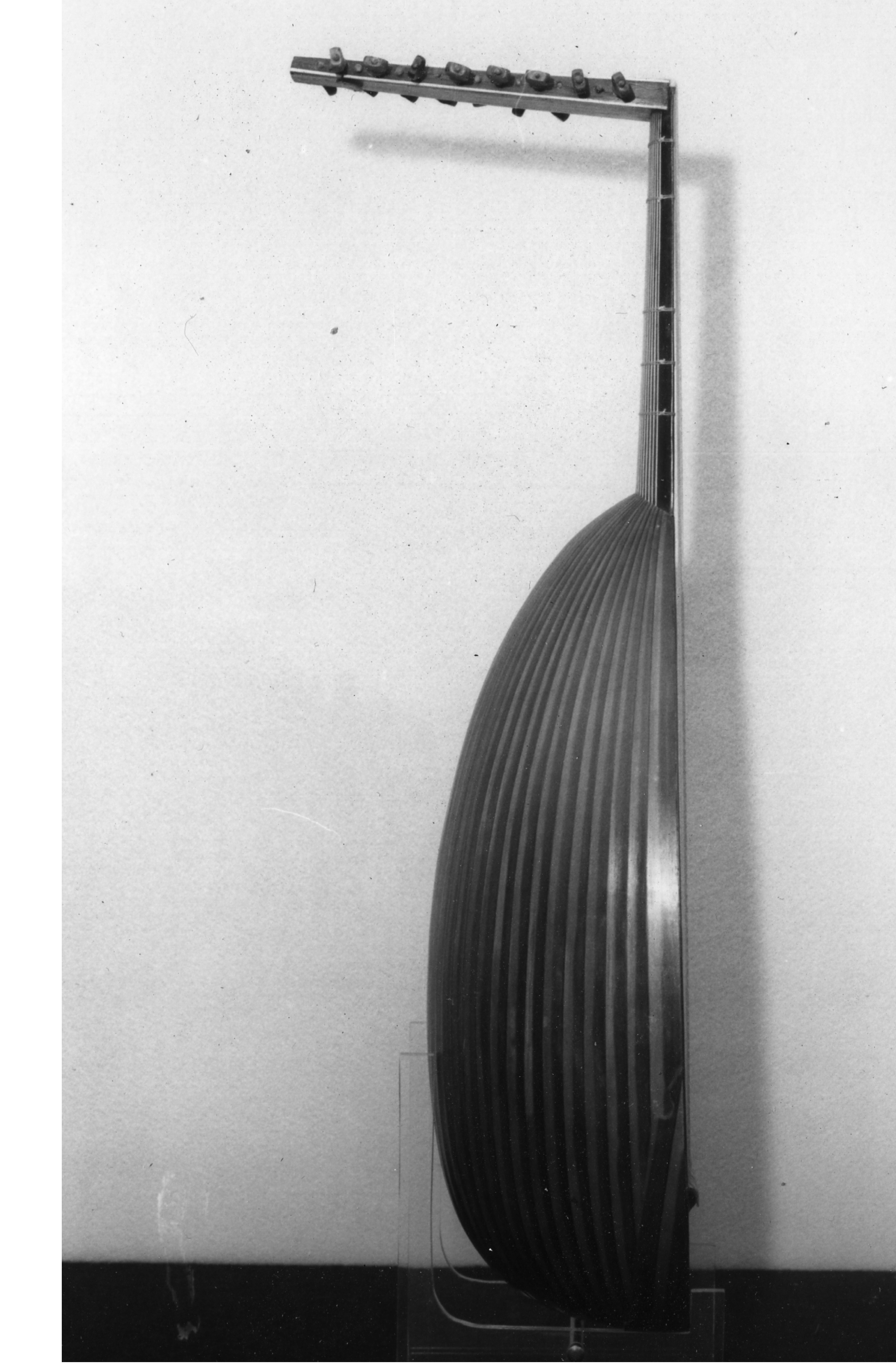

And

this monster by Giovanni Tesler made in 1615 has 65 ribs. They are in fact

heartwood/sapwood but the filthy varnish has obscured the contrast. It is now

in Dresden Museum and has been restored so if you visited the museum you’d be

able to see the true effect.

Where

were these yew ribs coming from? And here we go back to the Füssen family

connections which so many of these German Venetian lutemakers maintained. Let

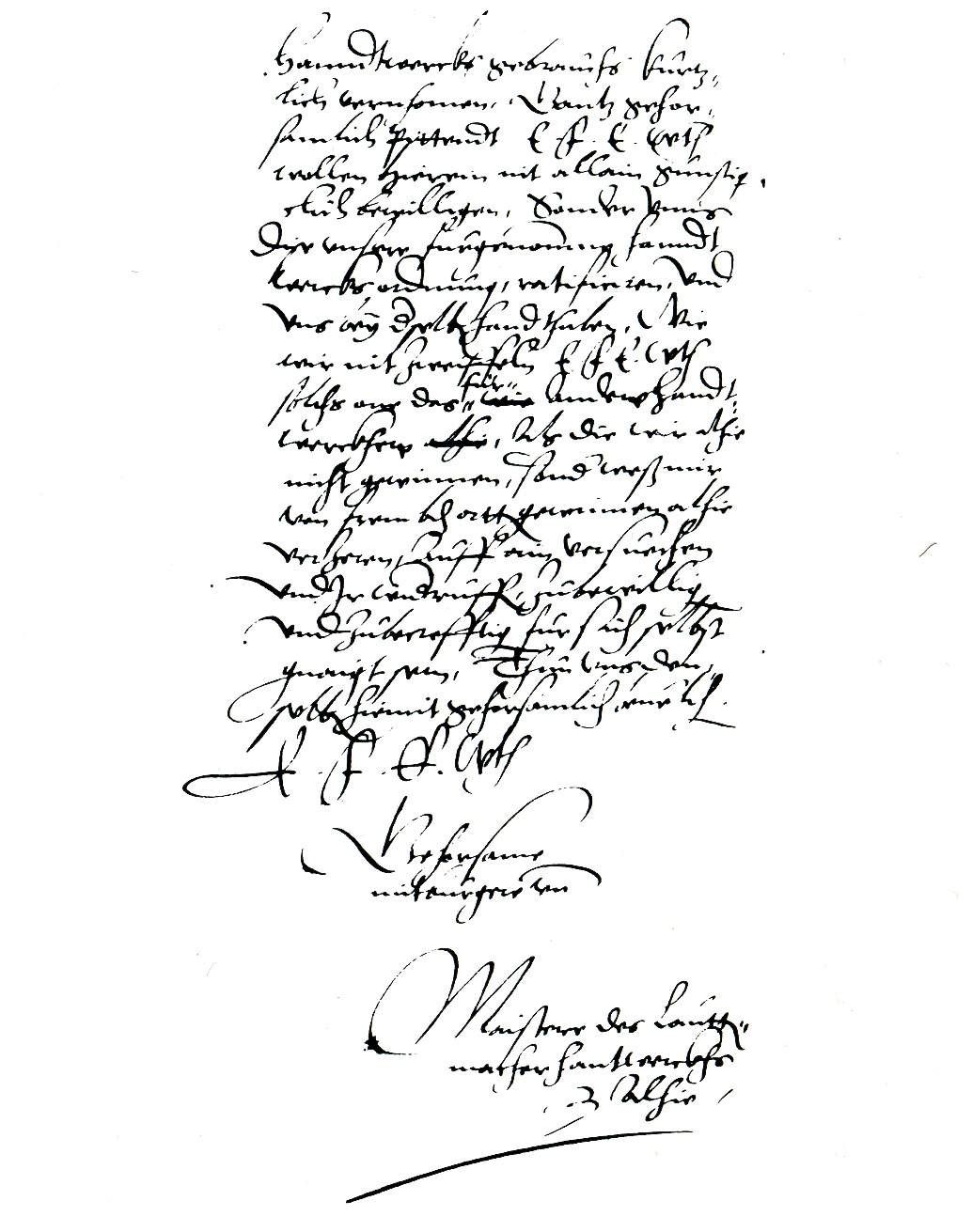

us look at the Guild regulations drawn up in 1562 for regulating the Füssen

lutemakers.

The

first of its kind (the second is a Parisian guild of 1599) Amid the many

detailed regulations about who can take apprentices and how long these

apprenticeships shall last [5] and how many years [3] he must be a journeyman

before becoming a master there is this last point:

“Finally, a number of citizens who have not

learned the trade here have dared to buy

lute

staves and to plane them and sell and brand them independently. This, however,

is

not only a burden for us and hinders us in competition with other towns, but

also

damages

our good name; therefore, in the future no one, no matter who, shall be

allowed

to practice this branding. Rather, he shall be put out of business by the guild

and

also punished according to the judgment of the guild, unless he has learned

this

craft

properly and honestly and has become a member of the guild.

Wherewith Your Honors have heard in brief

the summary of our craft customs.

Obediently

requesting, Your Honors shall not only herein graciously approve, but

also

ratify the guild regulations we have drawn up and support us in carrying them

out.

Because we, in contrast to other craftsmen, do not earn money here, but rather

we

spend here what we earn in other places, we do not doubt that it is in Your own

interest—as

an experiment and subject to your revocation—to approve and empower

[

these regulations].

Herewith obediently submitted,

Your Honors' obedient fellow citizens,

Masters of the lute maker's guild here

This

was at a time when there were 20 workshops

in Füssen complete with masters, journeymen and apprentices all in a

town of 2000 inhabitants. Adolf Layer in his book Die Allgäuer Lauten-und

Geigenmacher, Augsburg 1978, even makes the point that these restrictive

practices were another factor pushing some of the most enterprising makers to

move and seek work abroad.

Then

in 1606 these regulations were re-issued in a revised form which added the

stipulation that only legitimate sons of subjects of the Augsburg bishopric

could be taken as apprentices and that journeymen who had trained elsewhere

(Italy??) had to work at least two years for a Füssen master before they could

submit their “masterpiece” for approval.

Otherwise they could apply to become a master if they were able to marry

either a daughter or a widow of a Füssen master. All newly appointed masters had to offer

their lutes for sale to the guild before they could be sold abroad. And finally whoever remained unmarried was

not allowed to sell lute ribs but must instead remain as a journeyman in the

workshop of a master.

It

seems clear that cutting and preparing lute ribs for export was actually a

major part of these Füssen workshop’s activities. It also sounds, reading

between the lines, as if they were becoming increasingly defensive and insular

in relation to other centres of lutemaking that they perceived as a threat.

Confirmation of this might be the regular printed labels of Raphael Mest:

“Raphael Mest in

Fiessen, Imperato // del Misier Michael Hartung in Pa- // dua me fecit, Anno

16[ms]33”

These

make great play of having trained under Michael Hartung in Padua, surely as a

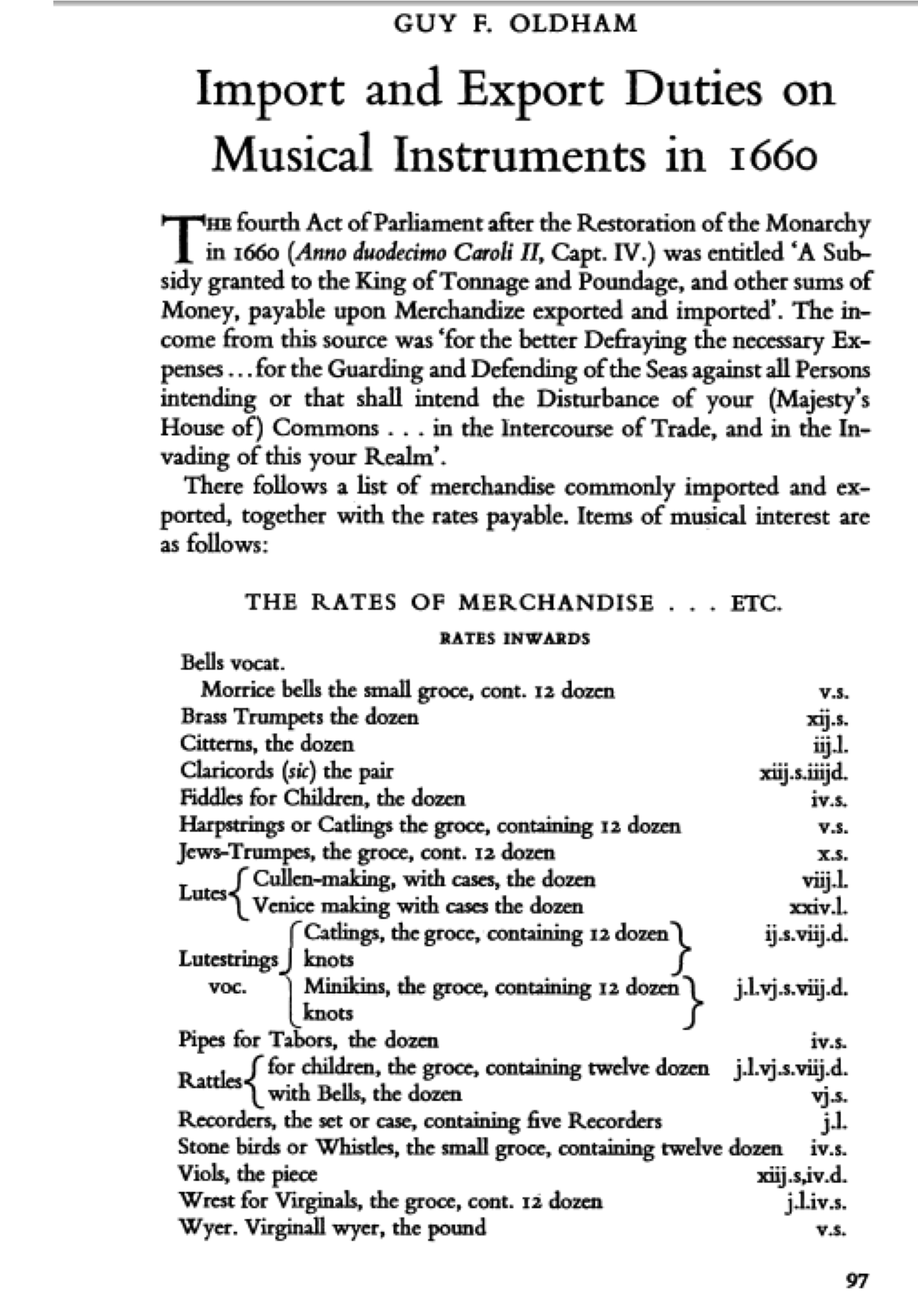

selling point. Further confirmation are the customs duties payable in the port

of London where “Cullen-made” lutes, that is lutes shipped through Cologne,

predominantly Füssen lutes, are shown over a period of nearly 80 years from

1582 - 1660 to be worth a third to a quarter of the price of “Venice-made”

lutes. And that both sorts were commonly shipped and taxed in units of a dozen,

so a considerable trade.

1660

Port of London duty charges

No

wonder the Füssen guild were defensive and Raphael Mest wanted some reflected

Italian glory.

But

there was a further, perhaps surprising, threat to the Füssen trade in lute

ribs. That very contrast between yew sapwood and heartwood which was so

attractive for the lutemakers had also a structural significance for making

powerful longbows. The sapwood is very resistant to tension while the heartwood

is very resistant to compression, so using the wood with the sapwood on the

outer face of the bow effectively produces the equivalent of a modern composite

bow. A bow of enormous power and rapid firepower that was still greatly

superior to the available muskets at the time we are concerned with. The trouble

was that Europe was running out of good straight yew, the Bavarian yew was

renowned to be some of the best and so the wealthy arms trade was in direct

competition with our lutemakers. England had been a major importer of yew bow

staves for several centuries: in the time of Richard III no wine could be

imported from Spain unless the ships also brought 10 staves of yew for every

barrel of wine, and in 1514 HenryVIII “sent men of science into Spain who chose

10,000 yew staves which were marked with the Crown and Rose, and were the

goodliest ever brought into England”

(Latham, Wood from Forest to Man 1964 p. 74). This demand created

a market and the wood dealers had to put in bids to the various authorities in

Bavaria, Tyrol and Austria for an Eibenmonopol, the yew monopoly.

From

Fred Hageneder, Yew a History, Stroud 2011

It

was a huge and lucrative trade, in 1510 Henry VIII, again, agreed to buy 40,000

bow staves from the Doge of Venice at £16 per hundred, and in 1521 the Austrian

monarchy demanded 5 Rhineland guilders per 1000 staves and Balthasar Lurtsch

bought 20,000 staves. The Nürnberg Fürer company, who held yew privileges in

South Germany and Austria, are calculated to have exported 1,600,000 staves in

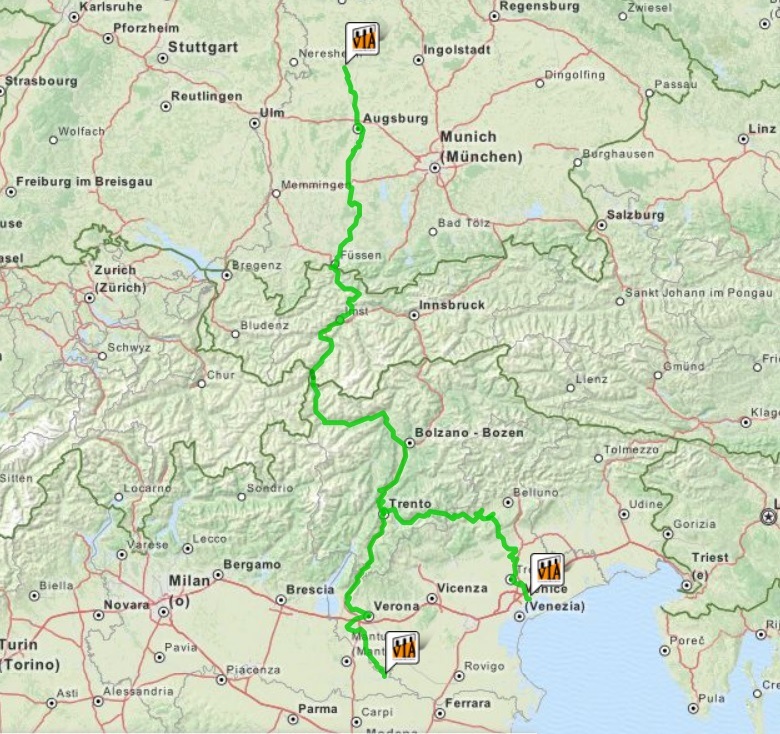

the period 1512-1592. This map of the export transport routes for yew bowstaves

reminds us of the infrastructure needed, and of course that it would be almost

identical to the routes used for finished lutes.

However

what it conspicuously left out was the Via Claudia Augusta route carrying

finished lute ribs. So I have added this in green.

From

Fred Hageneder, Yew a History, Stroud 2011

So

it is not surprising that this rival, well-funded, demand should pose a threat

to the Füssen lutemakers who were selling prepared lute ribs to their relatives

in Venice. It came to a recorded head in the years 1609-12 with a long and

complicated exchange of letters and pleas from the Füssen guild to the Duke of

Bavaria and the Archduke of Tyrol and

the Prince Bishop of Augsburg, trying to prevent a Dutch dealer, Walthauser von

Mühlheim, from repeating his felling and export of a large quantity of yew from

the Ettal mountains for sale to England and even to the infidel Turks (who had

a recent treaty with the Netherlands). They also complained of the sly dealings

of two who had picked out the finest and longest of the lute ribs which had

been made by the official day-workers in the previous years, and sent these to

Venice, Verona and Padua, and then had sent the shorter ones to Füssen and even

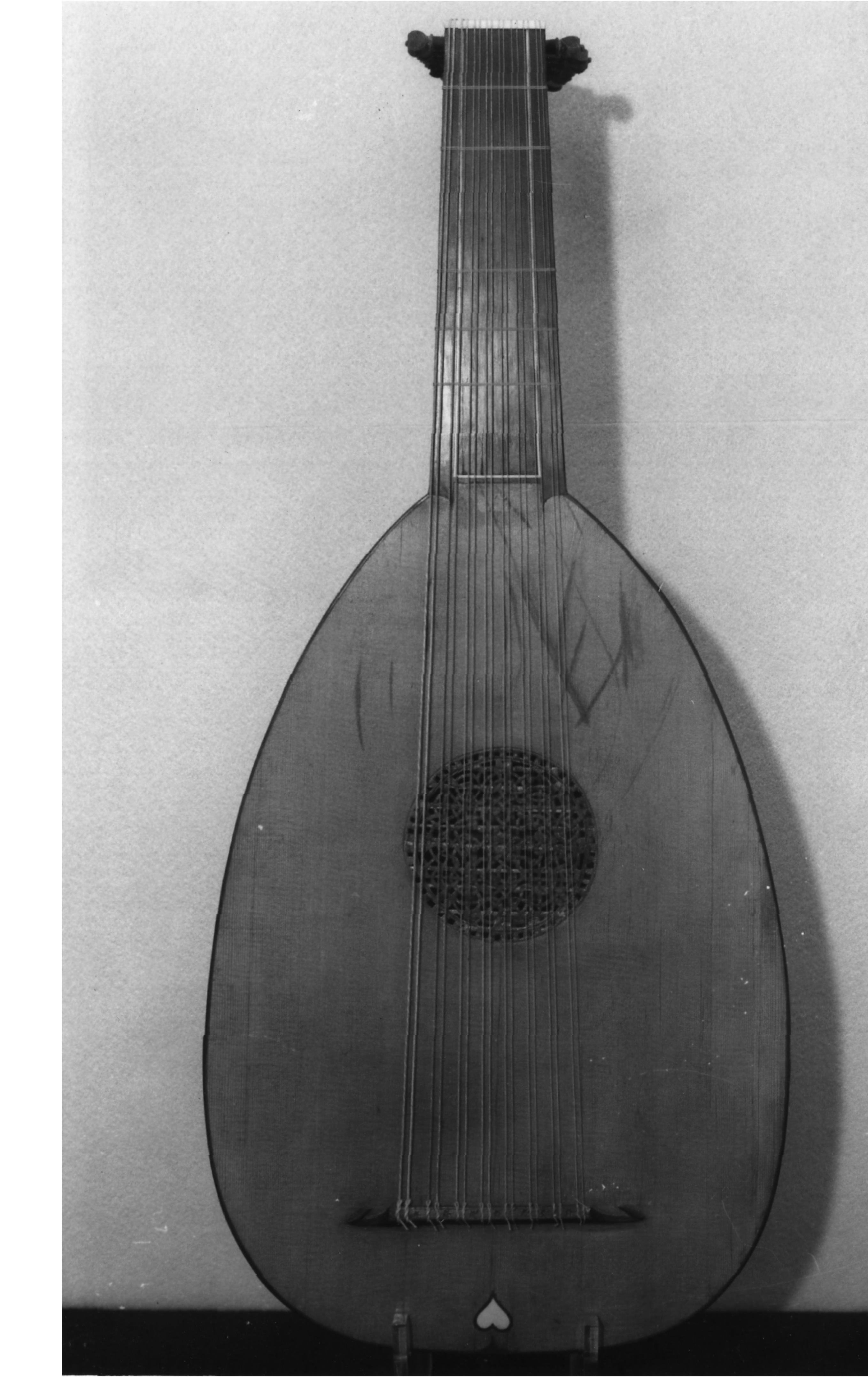

sold these at a higher price. One of the prime movers of the initial plea was a

prominent Füssen maker Mang Hellmer, two of whose lutes have survived, both

made of striped yew. This is the one in Darmstadt Museum

Lute

by Mang Hellmer, 1609 Füssen Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesmuseum (Kg 67:104)

Photo, David Van Edwards

In

brief the injunction was successful, but then Mang Hellmer himself went behind

the backs of the other makers and paid 100 guilders to Duke Maximilian for a

monopoly of yew felling for himself and in 1612 took 5 cartloads of yew

bowstaves to the market in Frankfurt. He was betrayed by his own brother and

the makers complained again, including the significant words “not only for us

poor craftspeople and our children’s children, not only here in Füssen but also

all the lute makers in Italy, where one sends the lute ribs...” (Layer, op cit.

p.23)

The

depredations of the arms trade and the lutemakers mean that there are now no

significant stands of yew in the whole of Europe and it is a protected species

over much of the continent.

Although

I am happy to blame most of this on the arms trade, the numbers of lutes

produced must have been quite staggering when we consider that just a one day

snapshot of Laux Maler’s workshop shows over a thousand lutes while only six

have survived and 360 Moises Tiefembruker lutes have come down to two. And these are only two of hundreds of

workshops producing lutes for at least 150 years. One would have to make far

too many assumptions to calculate anything like a reliable figure, but just a

back of envelope guess, using very conservative assumptions, suggest over 15

million lutes and, if the ratio of surviving lutes is applied, that makes

3,896,103 yew lutes, say 77 million yew ribs.