An Illustrated History of the Lute

Part 2

By 1500 the first written records confirm the existence of several families making lutes as a trade in and around Füssen in the Lech valley. Most of the famous names of 16th and 17th century lutemaking seem to have come originally from around this small area of Southern Germany. By 1562 the Füssen makers were sufficiently well established to set up as a guild with elaborate regulations which have survived.(see Bletschacher, 1978, and Layer, 1978) A careful reading of these regulations reveals how much they were predicated on the idea of export. They also show an organised tendency to keep the trade within individual families, which resulted in much inter-marriage. This was a powerful force for continuity which clearly lasted for centuries. However the number of masters who could set up workshop in the town was limited by the Guild regulations to 20, so there was a built-in pressure for emigration. It was also just this area which was devastated first by the Peasants war of 1525, the Schmalkald war and finally by the Thirty Years War which killed more than half the population of central Europe. Small wonder then that lutemakers, who already had international connections, moved out in such numbers.

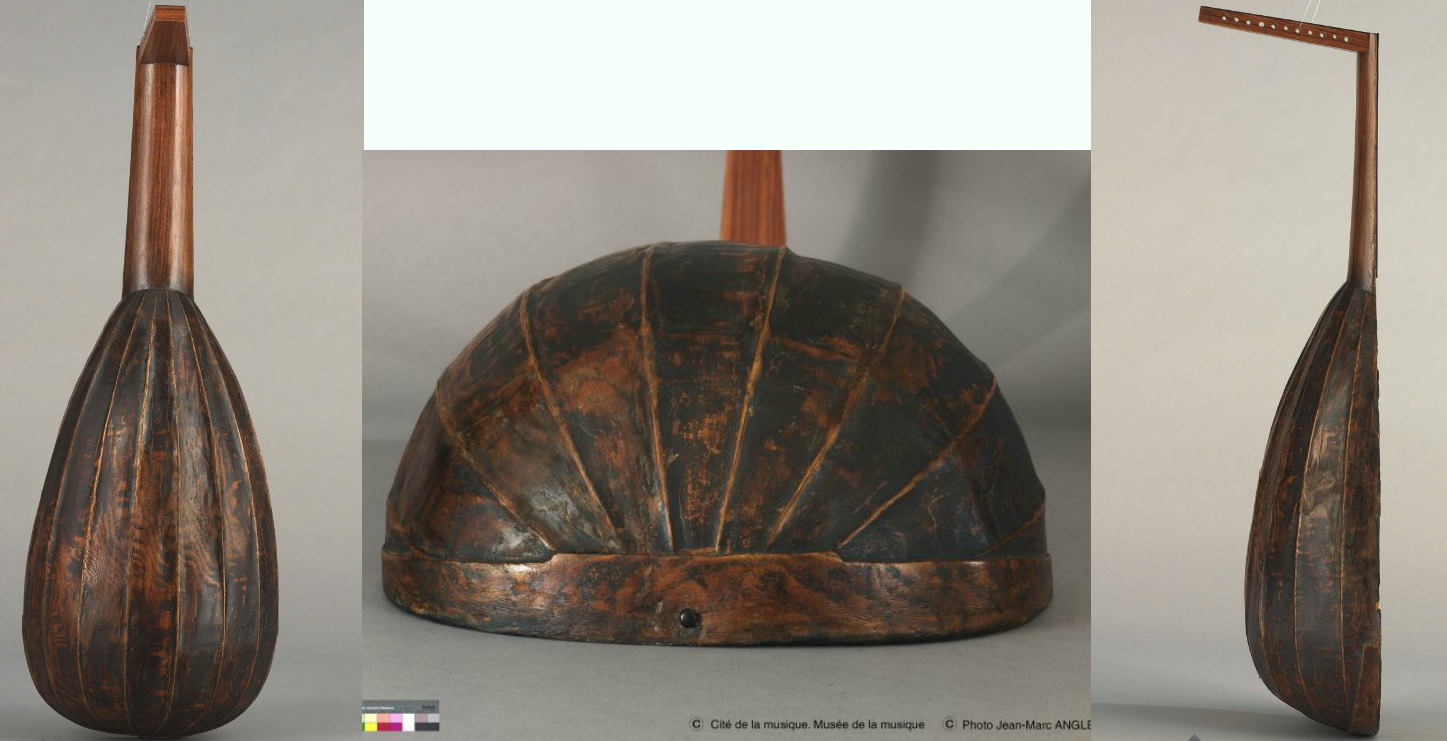

Paris, Musèe de la Musique, (E.2005.3.1) © Photo Jean-Marc Angles

An original Maler lute back with schematic neck to show the possible form of the original instrument. The back is made with 9 ribs of figured ash and has a reddish varnish.

Many settled in Northern Italy, no doubt attracted by the country’s wealth and fashion but also perhaps by the access to exotic woods imported via Venice. The tradition of inter-marriage meant that they remained as colonies of Germans and did not become much integrated into Italian society. Already by 1518 Laux Maler (see Pasqual, 1999) was well established as a lutemaker in Bologna, by 1530 he was a property owner of considerable substance and had built up an almost industrial scale workshop employing mostly German craftsmen. The inventory compiled at his death in 1552 lists about 1100 finished lutes and more than 1300 soundboards ready for use; his firm continued trading until 1613. Among several other lutemakers in Bologna were Marx Unverdorben (briefly) and Hans Frei. The main characteristic of their lutes is a long narrow body of nine or 11 broad ribs with rather straight shoulders and fairly round at the base.This form is remarkably close to that proposed by Bouterse (1979) in his interpretation of Persian and Arabic manuscripts of the 14th century. The chief difference is that these Middle Eastern descriptions, like Arnaut’s, indicate a semicircular cross-section, whereas the instruments of Maler and Frei are somewhat ‘more square’. Often made from sycamore or ash. they remained highly prized as long as the lute was in use, but became increasingly rare as time went on. No unaltered example is known to have survived, for their prestige was such that they were adapted (sometimes more than once) to keep abreast of new fashions. They have all been fitted with replacement necks to carry more strings. Sometimes, indeed, the vaulted back is the only original part remaining. (see Downing, 1978)

In Venice, as in Bologna, the German colony kept to its own quarter with its own church. By 1521 Ulrich Tieffenbrucker is recorded as present in the city, and for the next hundred years the Tieffenbrucker family, Magno I, Magno II and Moises, as well as Marx Unverdorben and Maler’s brother, Sigismond, dominated lute-making in the city (see Toffolo, 1987). The name Tieffenbrucker was from their original village of Tieffenbruck, but their instruments are usually signed Dieffopruchar and regional spellings abound with variants such as Duiffoprugcar and even Dubrocard. Another branch of the Tieffenbrucker family settled in Padua, including Vendelio Venere, who has recently been discovered to be Wendelin Tieffenbrucker, son of Leonardo Tieffenbrucker (see Kiraly, 1994 and 1995). Michael Harton also worked in Padua and may have been taught by Venere. The typical body shape of these Venetian and Paduan lutes was less elongated than that of Maler and Frei, with more curved shoulders (fig.9a, c-f). The first examples had 11 or 13 ribs, but later the number was increased, a feature associated with, but not exclusive to, the use of yew, which has a brown heartwood and a narrow white sapwood. For purposes of decoration, each rib was cut half light, half dark, which restricted the available width and required a large number of ribs, sometimes totalling 51 and even more. The yew wood was supplied from the old heartland of lutemaking in South Germany, and cutting the ribs for Venetian makers became a valuable source of winter employment there. (see Layer, 1978)

Photo by Stephen Murphy

A lute by VVendelio Venere (Wendelin Tieffenbrucker) with a multi-rib yew back, though in this case it is heartwood only with maple lines between the ribs.

The use of geometrical methods of lute design has already been mentioned, and it has been found by several writers (Edwards, 1973; Abbot and Segerman, 1976: Söhne, 1980; Samson, 1981; Coates, 1985) that the shape of these instruments can readily be reproduced by such means; this may account for the similarity in basic form between instruments of different sizes and by different makers. By comparison with the modern guitar, these early lutes, whether of the Bolognese or Paduan type, are distinguished by the lightness of their construction. The egg-like shape of the lute body is inherently strong and does not need to be built of very thick materials. Although the total tension of up to twenty four gut strings (for later lutes) can be as much as 70 -80 Kg, the well-barred thin soundboard withstands this pull remarkably well. Though in the 17th century, as the Constantijn Huygens correspondence makes clear, it was routine to re-bar old lutes as part of their renovation this may be more to do with alterations in barring layout than structural weaknesses.

The instruction to tune the top string as high as it will stand without breaking is given in many early lute tutors, (though not by Dowland or Mace) and is a practical matter. For if the highest string is lowered for safety's sake much beneath its breaking point, the basses will be either too thick and stiff or, if thinner, too slack to produce an acceptable sound. Wire-wound bass strings which could ease this dilemma by increasing the weight without increasing the stiffness are not known to have been available until after 1650, and apparently not much used thereafter either. Therefore, as the breaking pitch of a string depends on its length but not on its thickness, the working pitch of a given instrument is fixed within quite narrow limits.

In the second half of the 16th century there was a tendency to build instruments in families of sizes, and thus pitches, roughly corresponding with the different types of human voice. The lute was no exception. Examples of the variety of sizes available at about 1600 are the instruments shown in Fig 9. Magno Tieffenbrucker, Venice 1609, 67cm (fig. 9a), Wendelin Eberle, Padua, c.1580, 29.9cm, 44cm, 44.2cm (fig. 9c-e), VVendelio Venere, Padua, 1582, 66.6cm (fig. 9f), Michael Harton, Padua, 1602, 93.8cm (fig. 9g) Strictly speaking, the smallest of these (fig.9c) should be called a mandore (see MANDOLIN, §2).

In England the nominal a’ or g' lute was known as the 'mean', and was the size intended in most of the books of ayres, unless otherwise specified. The only other names used in English musical sources are 'bass' (nominally at d’) and 'treble', which is specified for the Morley and Rosseter Consort Lessons. The pitch of these “treble” lutes implied by the other parts was also g’ but there is a possibility (see Harwood, 1981) that this music was to be played at a pitch level a fourth higher than that of the mean lute. This nomenclature of ‘treble’ has caused some interest and put together with a number of specifically English pictures of small-bodied long-necked lutes may indicate a particular English variant. (see Forrester, 1994)