DAVID VAN EDWARDS

|

In Autumn 1946 violinist Aenne Brugmann joined the Gerwig-Gerstein-Koch trio to play Haydn’s Cassation in C major and Walter Gerwig wrote to his wife:

|

BOW CATALOGUE 2024

To see the complete list of bows in stock, click here.

Most of the standard bows are in stock and can be sent straightaway, special orders or bows out of stock can usually be made within two or three weeks.

To see a short list showing the range of players using our bows, click here

The Smokehouse, 6 Whitwell Road, Norwich NR1 4HB, England

Telephone: + 44 1603 629899

VIOLA DA GAMBA BOWS

These I make in two forms:

1. Renaissance. A rather pointed, shallow headed bow which suits rapid renaissance divisions, gives a very quick, rather sharp articulation and little sense of floating or sustain; the bow obeys the hand exactly and adds nothing.

Or with a screw adjusted frog as in the modern bow. This is inauthentic but does offer the considerable convenience of allowing for changes in the weather.

Or with a screw adjusted frog as in the modern bow. This is inauthentic but does offer the considerable convenience of allowing for changes in the weather.

2. Baroque. A deeper headed form which gives a sense of float and grace, most players find it very satisfactory for the normal run of consort music.

These too can have either a clip-in or a screw frog, though the screw adjustment is more normal for these bows nowadays.

Both of these can be made straight, in which case they will take up the convex curve seen in almost all the pictures of the 17th century, or they can be given a reverse [concave] curve like a modern violin bow, which will give a much tighter feel to the hair and will seem to "grip" the string better. Obviously players of modern instruments will feel more at home with this form and it does enable the solo repertoire to be played with considerable brio but it is probably anachronistic for the earlier part of the 17th century. The same bow given a reverse curve will feel completely different and can be made lighter for the same degree of hair tension, reaching the limit of this possibility in the modern violin bow. [Many players do not realise that even modern violin bows are made straight and then given their curve by bending with heat.]

The normal sizes are:

Bass 73 - 76cm stick length; which gives typical weights of 65 - 70 grams for pernambuco, and 75 - 88 grams for snakewood.

The same basic shapes and options apply to tenor and treble bows but with typical sizes of:

Tenor 67 -72 cm stick length; which gives typical weights of 45 - 55 grams for pernambuco, and 68 - 73 grams for snakewood.

Treble 61 -67 cm stick length; which gives typical weights of 38 - 45 grams for pernambuco, and 45 - 55 grams for snakewood.

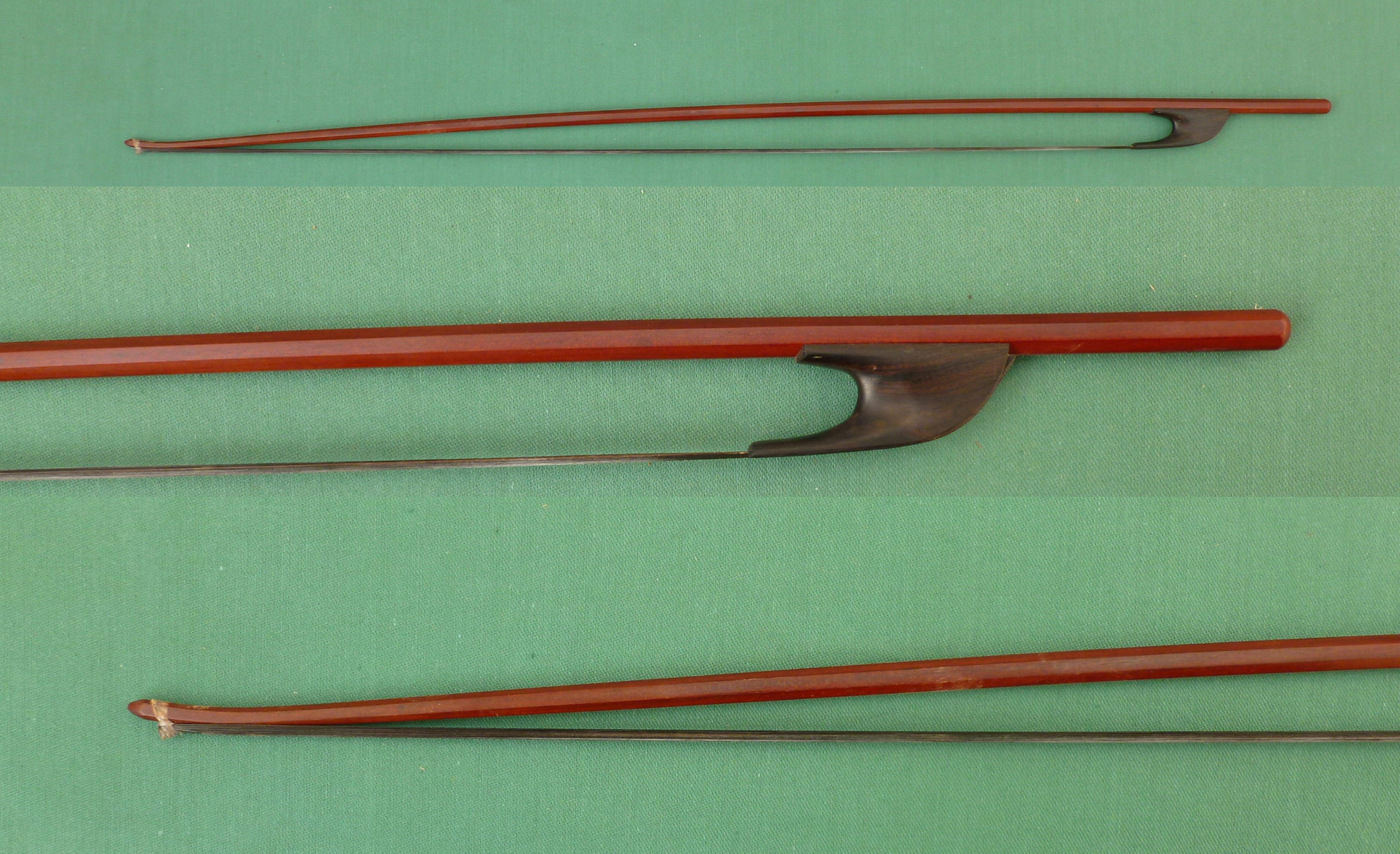

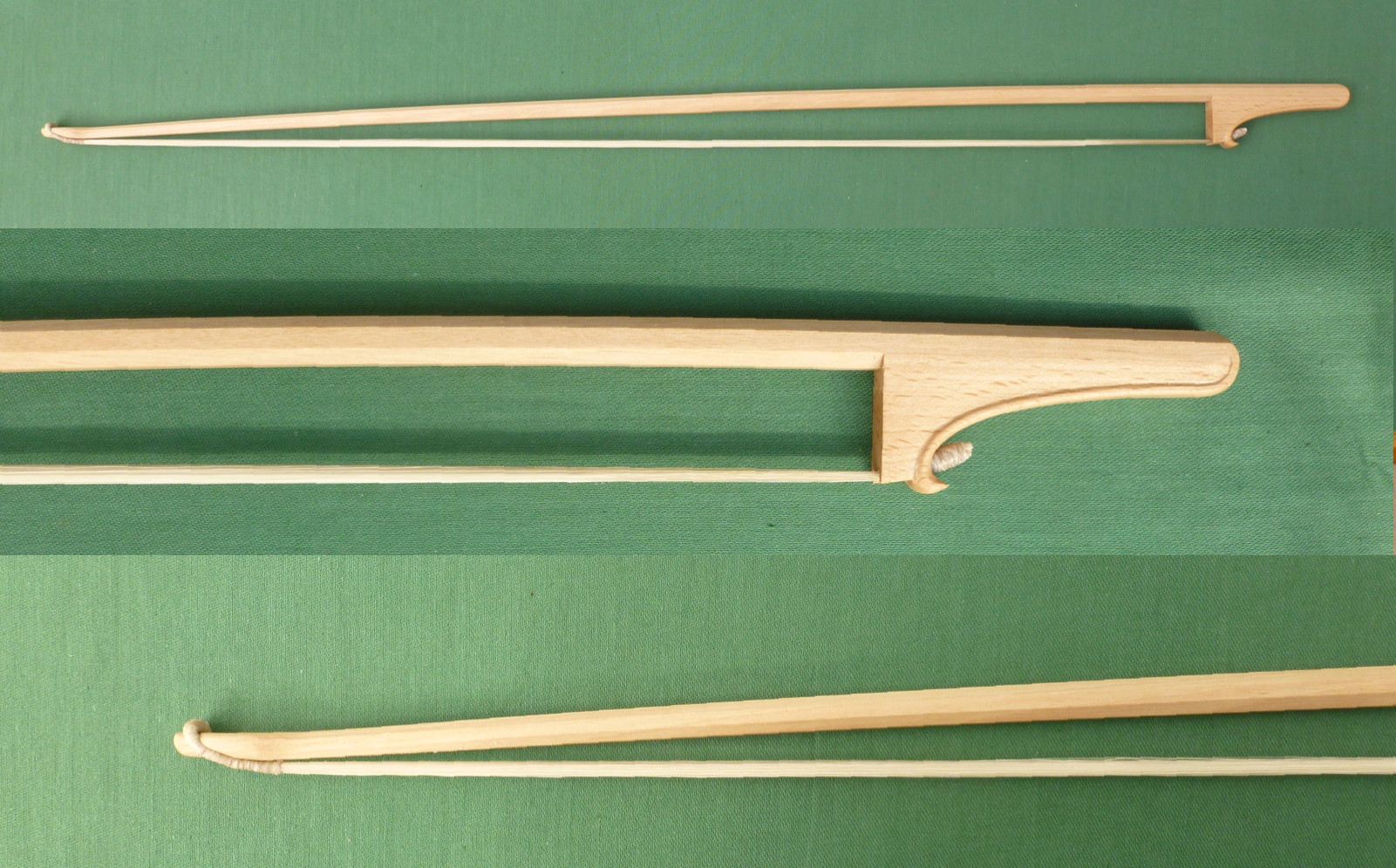

Here for example is a typical clip-in frog tenor bow.

THE MARAIS BOW

There was a special development of the bass viol bow in France in the 17th century for playing the expressive solo repertoire for the 7 string bass viol. It seems to have been somewhat longer with a long button and an elongated head. This has come to be known in modern times as the Marais bow because there are two well-known portraits of this famous player which clearly show him playing the same bow at different times of his life.

And here is a close-up of the bow from the first picture.

Many makers have made their own versions of this bow and here is ours in figured snakewood with boxwood fittings. The stick length is 762mm and the weight is 91 grams. The stick is straighter when fully up to tension.

One of my Marais bows can be heard and seen here wonderfully played by Ibi Aziz. Youtube video

EARLY VIELLE AND FIDDLE BOWS

I have recently developed two different styles of medieval bow:

Circa 1520 based on a painting in Perugia by Bernardino di Mariotto

Incoronazione della Vergine. 1528, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, Perugia

As you can see it has no head at all and the black hair is simply tied to the end of the stick. Alas the frog is not visible but it was most likely a clip-in type. However I have developed a simple concealed ratchet device for these bows which means that the hair can be adjusted for different tensions and to account for any changes in humidity. In spite of its very simple form it plays remarkably well and feels very lively.

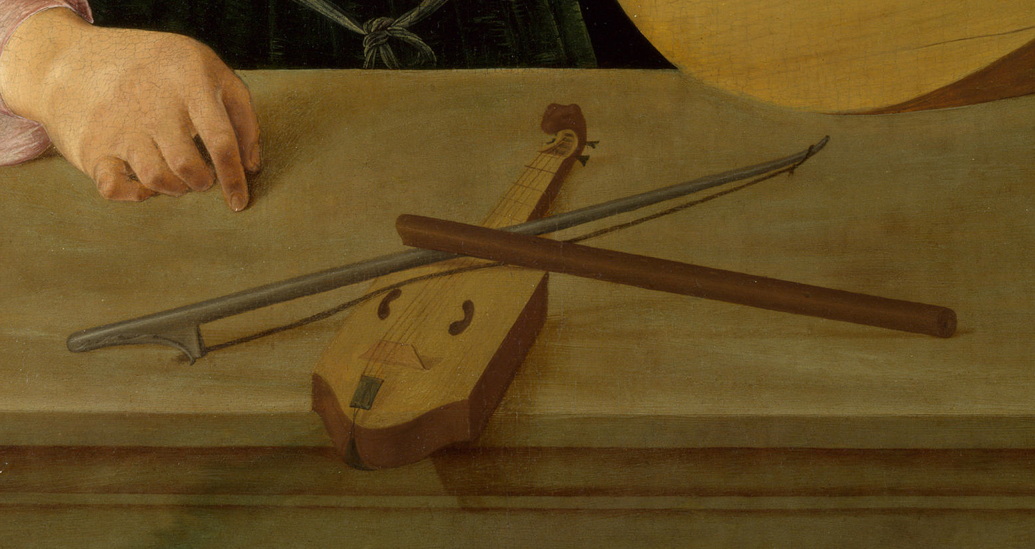

[c.1550] with no head and the hair fastened to the tip in the same way as an archery bow of the period. This is based on the bow shown in the da Costa painting in the National Gallery, amongst others, and has been found to work surprisingly well. The frog is completely fixed and the bow is strung and unstrung after playing, just like an archery bow.

Detail of A Concert by Lorenzo Costa c.1550. National Gallery, London NG 2486

Historiated initial from a choir book: King David kneels in prayer (c.1490-1500) Bologna or Rome, Italy

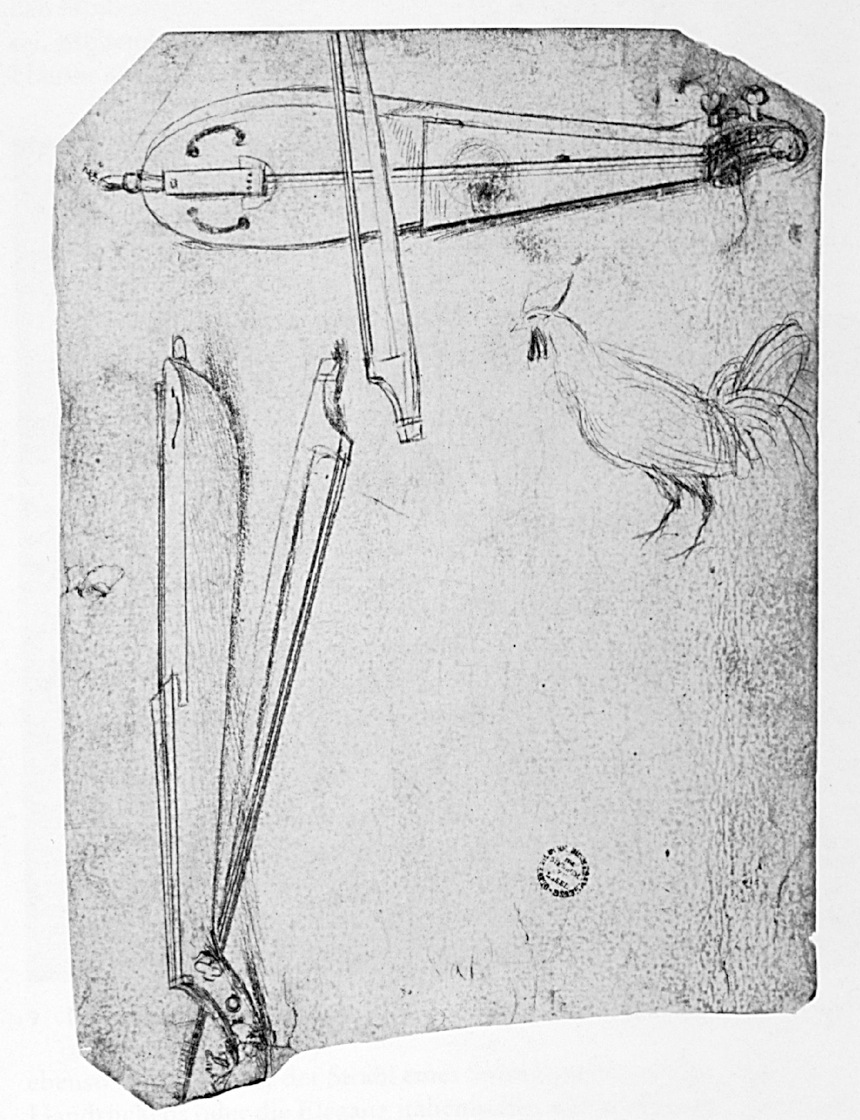

This is a drawing by Hans Holbein c.1513 currently in the Kunstmuseum in Basel showing very much the same frog type. The lines at the back end of the frog raise an interesting possibility that these frogs were not glued on but held in a rebate and tensioned by tightening some cords at the back. It’s a pity he didn’t show the tip of the bows! And looking again at the Book of Hours miniature it too looks as if there are cords holding the back end of the frog, but this is demonstrably NOT true of the Costa painting. At some stage I will try it as a system.

This detail of a print of 1524 by Lucas van Leyden shows how the tip works.

My version.

BAROQUE VIOLIN, VIOLA AND CELLO BOWS

These have the same variations of head and curve as the gamba bows but the pointed, shallow head form seems to have persisted until later for violin and viola, though by the time of Leopold Mozart's treatise on violin playing (1756) the baroque form seems to predominate. Early cello, bass violin and double bass bows seem to have had the deeper head form from about 1600 on. If you are using all gut bass strings for these larger instruments you may find that they speak more quickly with black hair, which is coarser and seems to grip the string more securely.

Normally I make baroque violin bows with a stick length of 68cm, viola bows at 67cm and baroque cello bows at 73cm; but players' requirements are so various that I am very happy to make bows of any length.

The same comments about reverse curves apply as for gamba bows. In fact the differences between gamba and early violin family bows are very hard to determine and it is often very difficult to tell for which instrument any given historical bow was intended.

This is one of our typical violin bows with a screw-adjusted frog:

And this with a clip-in frog:

EARLY CLASSICAL VIOLIN, VIOLA AND CELLO BOWS

For the transitional period between the early baroque and the modern Tourte violin bow I have developed a graded series with gradually increasing reverse curves and head depths and gradually decreasing stick thickness. So, if you tell me roughly which period of music you intend mostly to play, or where on the spectrum of transition you would like your bow to be, I will do my best to make something suitable.

One of our transitional bows is based on the form of the so-called Stradivari bow which is featured in the Hill brothers' book. This has a nice gentle reverse curve and a fine delicate head clearly somewhere between the baroque and modern forms.

TRANSITIONAL VIOLIN, VIOLA AND CELLO BOWS

Transitional bows are also often known as Cramer bows after Wilhelm Cramer (1745-1799) a virtuoso violinist who made a big impact when he arrived in London in 1772, even though it is not known for certain what sort of bow he used!

What is clear from the surviving bows and some paintings and drawings of the period is that from the middle of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century players, composers and makers were experimenting with new sounds and techniques for stringed instruments. Bowmakers like Dodd, Duke and ‘Forster’ (Forster was a dealer who stamped bows with his name) in England and Tourte père, Duchaine, La Fleur and Meauchand in France were all, pre-François Tourte, trying out new ways of increasing tension in the bow hair and increasing the power of the bow without increasing its weight. These developments had their climax of course with the arrival of François Tourte who really reached the limit of what was possible with the available woods. However in these intermediate stages of development, where some aspects of the earlier bow forms were still present, distinct possibilities of technique were available which were closed off by the modern (Tourte) bow.

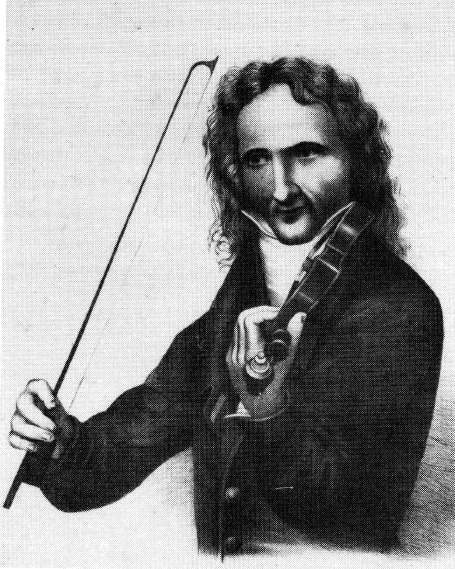

The most famous virtuoso of the period of course was Paganini and again it is not certain what sort of bow he used but he is shown in contemporary pictures playing two quite different styles of bow and anecdotally he was said to have had a favourite bow which he used in spite of it having been broken into several pieces and mended. However the supposed favourite bow preserved with his violin is unbroken!

Based on the contemporary engraving of Paganini shown above which shows the head of his bow clearly and on an anonymous bow in the Hill Collection in Oxford [No. 24] this bow is suitable for the 18th century virtuoso repertoire such as Tartini. It has a curved double-ended head, obviously transitional between the baroque and the modern form of head, quite elegant and very light. I show here a cello version in pernambuco.

Thus it is that these transitional bows are worthy of study in their own right and not just as poor attempts at a modern bow. For the music of the period, roughly 1750-1820, you may find they offer a delicacy and agility which suits the repertoire while still having more power than the earlier classical bow. They also blend in more tonally with other instruments of the period such as the fortepiano.

We have therefore chosen three or four historical bows to base our transitional bows on. These bows by Duke, Forster, Dodd and that great maker Anon, seem to represent the range of styles shown being used at the time. They are all subtly different in terms of balance and spring but all represent a new sound world from either the modern bow or the earlier Italian sonata bow. We hope you will enjoy trying them.

This one below is closely based on a beautiful bow by John Dodd c. 1800 (stamped Betts) which is featured in The British Violin: 400 Years of Violin Making in the British Isles by Tim Baker, John Dilworth, Andrew Fairfax as one of the best examples of his work.

And here is yet another John Dodd cello bow which is clearly heading further towards the modern Tourte bow.

See also the major article on transitional bows The Violin bow in the 18th Century by David Boyden, Early Music, Vol. 8, No. 2, Keyboard Issue 2, (Apr., 1980), pp. 199-212

See also the major article on transitional bows The Violin bow in the 18th Century by David Boyden, Early Music, Vol. 8, No. 2, Keyboard Issue 2, (Apr., 1980), pp. 199-212

BAROQUE DOUBLE BASS BOWS

These I make in the two forms for French and German grip players. Typically they are 670-700mm long and weigh between 137 -140grams in snakewood.

This is the German grip version:

And this is the French grip version:

CONSTRUCTION & WOODS

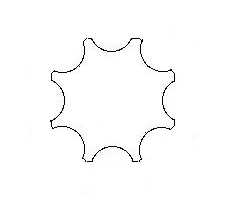

The bows are octagonal or fluted or round stick. The basic bows are octagonal, but to make them lighter or to feel more delicate, without much altering the the stiffness, they can be fluted from the tip to approximately the point of balance. This is an approximate cross-section of fluting

Alternatively they can be made round, leaving just a short length of octagonal section on which the frog runs. The differences are very slight but it seems that fluting puts a slight “edge” on to the sound while round sticks sound slightly sweeter.

Octagonal and round stick bows are the same standard price, but I do charge £65 more for fluting.

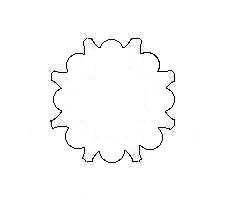

There is also the option of reeding the handle section, which is like a flute with semicircular ridge down the centre. This too costs an extra £50. This is an approximate cross-section of reeding.

This is very attractive but doesn't affect the playing characteristics of the bow, some people do find it has the effect of giving more texture for the fingers to grip. (All of these designs were originally “borrowed” from classical Greek architecture of columns)

Normally I make the fittings, frogs and knobs, from African blackwood (Dalbergia Melanoxylon) because it takes a higher polish than ebony and has a closer grain. However I also often use snakewood or fumed boxwood (Buxus Sempervirens) for the fittings. The choice is mostly aesthetic but boxwood is marginally lighter in weight as well as colour. Early bows very commonly had fittings made of ivory, which looks and feels wonderful but is now illegal to trade across borders. Amazingly, mammoth ivory from 10,000 year old fossilised Siberian mammoth tusks is available and legal but it is ferociously expensive and I'm not sure how ethical the trade from Russia is. The YouTube videos of the of its extracton make clear how difficult and bordering on illegal it is, so I don't keep it in stock. It does offer a way round the rules, but it is increasing in price dramatically all the time so please enquire about prices and be prepared to wait while I import a blank.

A mammoth ivory frog and button on a baroque violin bow.

This is an ornate design loosely based on one in the Hill collection (No 25)

All the normal frog designs can be made in mammoth, for instance:

I use stainless steel for the spindles which otherwise often rust. Screw adjustment of the frog is probably anachronistic for the earlier bows but it is a great convenience in allowing adjustment for changes in the weather, however I do also offer clip-in frog renaissance bows for those who like the feel of these. I have developed a new system of tensioning for clip-in frog bows with a small built in ratchet which allows for a small amount of variation to accommodate for changes in humidity. This is not such a large adjustment as the standard screw mechanism but it does do away with one of the major objections to clip-in frog bows without adding appreciably to the weight. This is an example:

CHARACTERS OF DIFFERENT WOODS

Pernambuco (Caesalpinia Echinata) This is an orange brown wood, heavy and very stiff and is the standard wood used for the modern violin bow. It was originally imported mostly as a dye wood and legend has it that Tourte was the first to notice its suitability as a bow wood. This is demonstrably untrue as there are many pernambuco bows from before Tourte's time, but it is true that after Tourte it became almost the only wood used for good bows. It produces a very bright, brilliant sound from the instrument. In my opinion it became popular in the age of the virtuoso violinists because is emphasises the upper harmonics of the notes and thus sounds more brilliant, but equally it’s harder to control. So like the repertoire of the time it is a high-wire act!

Snakewood (Piratinera Guianensis) is the other main wood used for bows, particularly earlier period bows. It is difficult to obtain and is ferociously expensive but it does make a wonderful bow. It produces a rich powerful sound and is much used by professional players of period instruments because of the volume it can produce. It is one of the heaviest, stiffest woods known, smooth and dark brown for the most part. However some snakewood has a decorative figure of irregular black patches which look a bit like the markings on a snake, hence the name. This figure varies from log to log, and also within each log, some parts are highly figured, some have a mild figure and other parts have virtually no figure at all. This is a representative selection of what we call in the stocklist description of each bow “highly figured”, “figured” and “unfigured”. These three pieces came from adjacent parts of the same log. It is very strange and beautiful but it adds nothing to the playing character of the bows, only to the cost!

Partridgewood (Caesalpinia Grenadillo) is closely related to pernambuco but quite different in appearance, being much darker brown with markings like the feathers in partridge wings and heavier. It seems a good substitute for those who like a heavier bow without excessive thickness but, because it is somewhat weaker I would only recommend it in the reverse curve form.

Ebony (Diospyros spp.) is surprisingly good as a bow wood. It tends to produce a very smooth sound, somewhat lacking in top edge, so it would be best used for instruments (or players!) which normally have a rather strident or harsh tone. Its jet black appearance is very striking.

The effect of ebony is to take away the upper harmonics of the notes so that a smoother more mellow sound is created, but at the expense of some of the expressive potential. In the long run an ebony bow sounds dull, uninteresting compared to snakewood and pernambuco. Pernambuco is the opposite, it lends the most brilliance to the playing, but has the problems associated with this potential; in sonic terms, it's a bit of a high wire act! No surprise that it became so popular in the 19th century heyday of the virtuoso. Snakewood is in many ways the ideal compromise for the baroque repetoire.

Greenheart (Ocotea Rodiaei) is actually rather more khaki than green, but it is a very good wood for the lighter bows. It used to be used for hand-made fishing rods because of its springiness and resilience, as well as for lock-gates and sea defences because of its toughness!

SOME REMARKS ABOUT BOWS AND HAIR

In general a bow has to resonate sympathetically with the instrument and this is affected by almost everything you care to name: weight and tension of strings, hair, bow, bow arm, soundboard, etc etc. So the best bow is the one that works best for you, and may not be the same as the best for the next player or instrument.

Beginning students may have bad habits, of playing position etc. or be insufficiently clear about what they're listening for, in which case the teacher's opinion on the bow, [preferably played on the student's instrument though] may be the most accurate and useful.

The ability of a bow to carry hair to a given optimum tension is determined by its stiffness. So a stiffer bow can carry more hair to the same tension than a weaker stick. Thus modern violin bows, with their very stiff geometry of reverse bend, can commonly carry 180 hairs whereas a bass viol bow is likely to have about 130 hairs. Therefore the number of hairs will vary from bow to bow, from wood type and curvature. If there are too many hairs for the bow they will feel slack. The weight of the hairs in any given hair band will act as a kind of 'inertia' to drive the string, and so in general the more hairs the louder, subject to the provisos above.

For large instruments with all gut stringing such as baroque cellos, large bass viols or bass violins, black hair is often better for getting the thick bass strings moving at the start of a note. This is because the individual hairs of black hair are thicker and thus have a greater area in contact with the string. The microscopic scales on the surface of the hair which hold the rosin and provide the 'stick-slip' grip on the string are also coarser and further apart in the case of black hair, and so, though often louder and quicker to speak, they may produce a rather coarse sound. If your large gut strings are slow to speak and rather feeble, it may be worth experimenting with black hair in your bow.

Try the bow on your instrument, preferably with a friend listening at a distance to compare notes on volume and clarity. Ignore the price ticket and concentrate on getting the best sound and then look at the price!

MY TERMS OF TRADE!

Players, their instruments and their teachers are so variable that a bow which suits one will not do for another, and both may be right! Consequently I send out my bows on approval for a week's trial and welcome them back with comments.

Bows are sent by registered or insured post in specially made screw-top tubes. Any bows returned should also be sent by registered or insured post in the original tube. And carefully wrapped to prevent the bow moving up and down in the tube!

Price, for standard bows:

£600 in premium seasoned pernambuco.

£600 in unfigured snakewood.

£625 in figured snakewood.

£650 in highly figured snakewood.

(click on the price to convert it to your own currency)

Fluting and reeding are both £75 extra for any bow.

Different payment methods

- The price in pounds (£) is for a cheque drawn on a British bank. This is the basic price, which includes insured postage within the UK and assumes the return of the empty posting tube.

- Those living outside the UK can use a bank draft drawn on a British bank, all banks have arrangements to enable this but they will charge you for the service. For this please add £13 to cover the cost of International registered post and the strong screw-top postage/storage tube which is yours to keep.

- It is also possible to pay using money transfer by Western Union (email me the code and I can pick it up as pounds in Norwich). For this please add £13 to cover the cost of International registered post and the strong screw-top postage/storage tube which is yours to keep.

- We have arranged for secure credit card payment via PayPal. If you wish to use this method, click on the “Buy now” button next to the bow you wish to buy to be taken to the shopping cart page where you should choose the appropriate shipping zone (UK, Europe or USA/World) You will then be taken to a secure page run by PayPal to enter your credit card details.

PayPal can accept all major credit and debit cards; payment can be made in pounds, euros or dollars.

PayPal then send both of us a confirmation email which I further acknowledge personally by email and post off your bow by insured airmail. It should take between seven and ten days to arrive depending on where in the world you live. If you have any trouble with the shopping cart please just email me and I'll set up a special button which by-passes the cart and takes you straight to the PayPal secure page.

(Just occasionally some people find that the shopping cart system at the start of the procedure doesn't work properly; if you have any trouble with it please just email me and I'll set up a special button which by-passes the cart and takes you straight to the PayPal secure page.)

If, after trying a bow, you do not like it for any reason at all, please return it at your expense by insured or registered post in the original posting tube and I will immediately either refund your original payment or send a replacement bow at my expense. It would be a help if you could telephone or email me to tell me what you are doing.

I hope this of some help and I look forward to hearing from you. If you would like more information or would like to order a bow please me

My postal address is: The Smokehouse, 6 Whitwell Road, Norwich NR1 4HB, England

Telephone from abroad is: + 44 1603 629899

Yours sincerely,

David Van Edwards

Return to the top of this bow page

Also to see the complete list of bows currently in stock, click here.

Copyright 2000-23 by David Van Edwards